A Report prepared by the Lead Adviser on Disability, Accessibility, and Inclusion

Dr Fiona Whittington-Walsh

Background

During the final exam period of spring 2024, KPU retained the services of LET’s a non-profit organization that provides low/reduced sensory spaces for a seven-day period as a pilot on the Surrey campus. The pilot was funded by the Provost, Dr. Diane Purvey.

The week prior to the exam period we advertised through emails to students and faculty. I received many positive emails from faculty elated at the news that we were providing low/reduced sensory space. Some of the email comments include the following:

This is fabulous! Thanks for sharing, and for helping organize this. Great to see this happening at KPU.

Wow! This is great…!

This is so thoughtful! Thanks for sharing…, I posted on Moodle and emailed all my sections ●J

This is amazing. Thank you… This is super cool!

This news brought tears to my eyes. What a terrific initiative! I will send this news off to my students.

This is great, thank you so much! If you have a social media sharable version of this, please let us know and we can share on our Insta.

That is excellent… My child …could have used something like this.

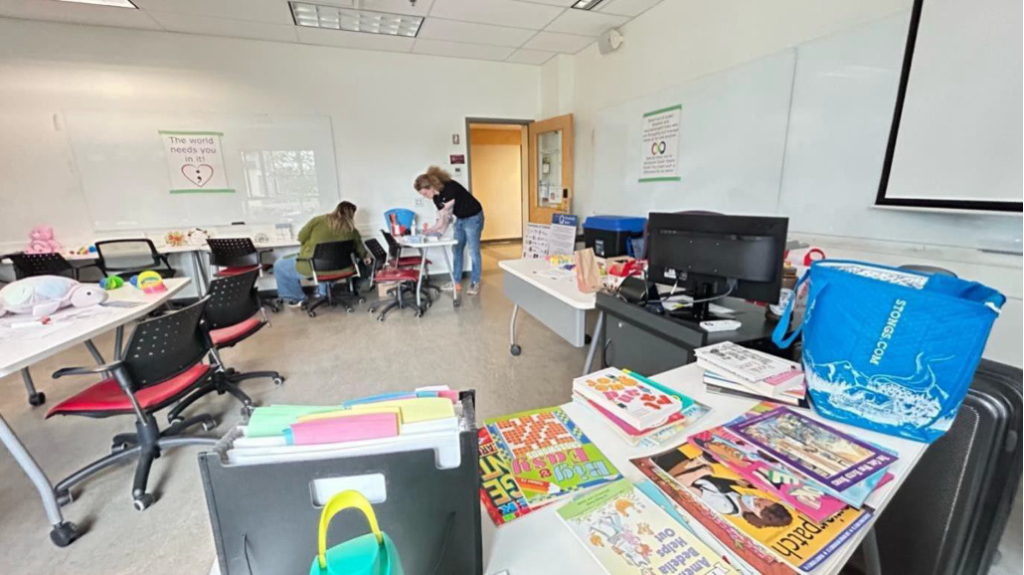

The low/reduced sensory space was held in Cedar 1015, down the hall from the Tim Horton/s. This location was central as it continues to be the main area where most students venture throughout the day. Cedar 1015 is a smaller classroom with couches and a carpet area at the back of the room. The room has large windows that can be opened. Windows are important in order to minimize artificial light and help facilitate a quiet calming space. Please see Appendix A for photos of the room set up.

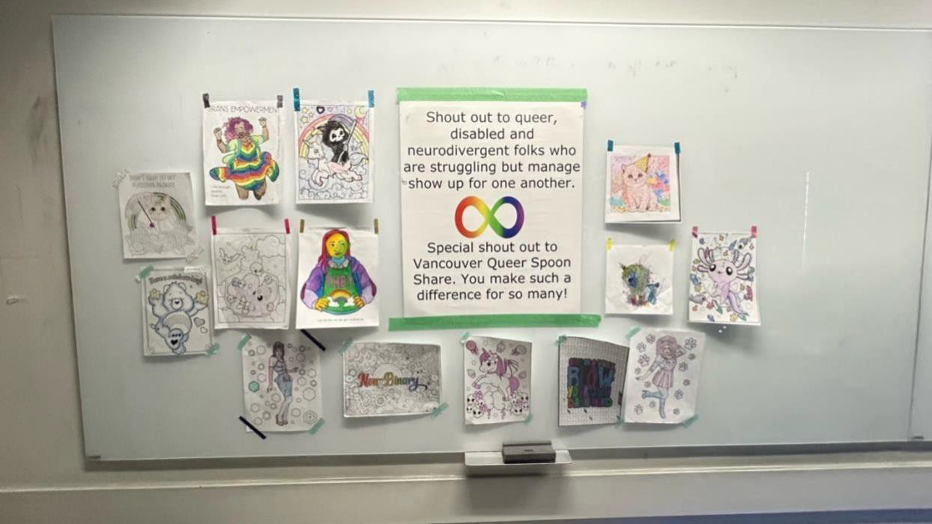

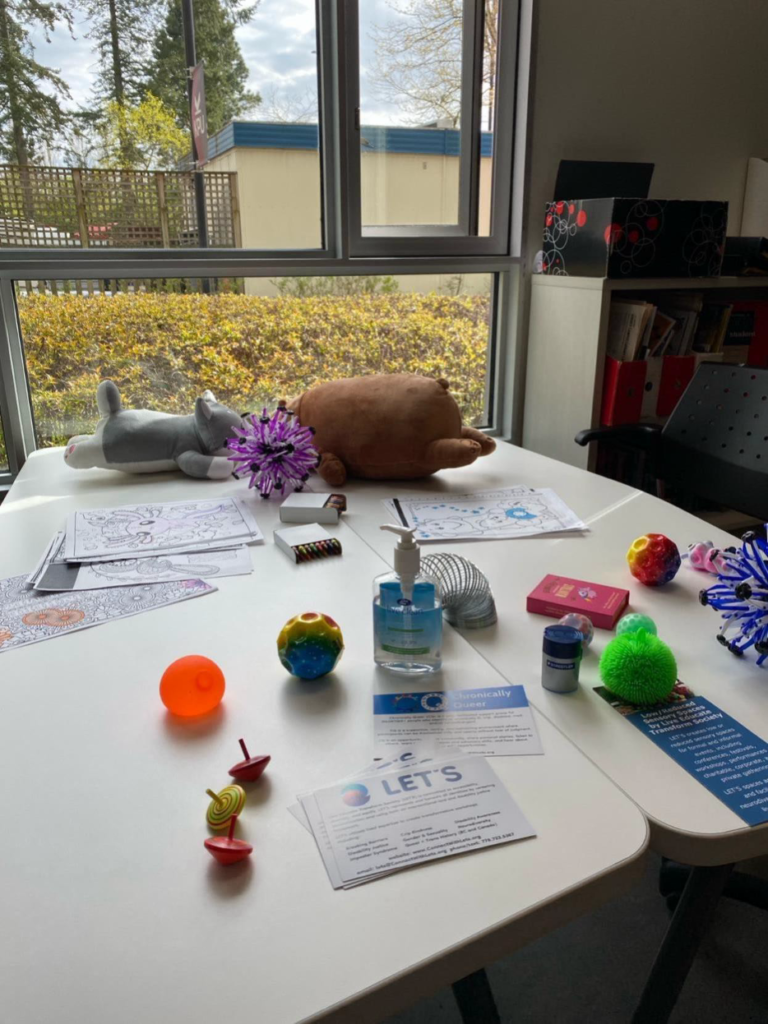

LET’s is fully equipped with stim toys, stuffies, markers, crayons, colouring pages, books, and posters adorned with positive messages to create an inviting space where people can go to relax, de-escalate, be safe, and regulate themselves.

During the seven-day exam period, over one hundred students visited the room often returning a second time bringing additional guests. During the first day, one student told LET’s staff the following:

‘I studied eight hours; slept four hours, and just took my exam. This room is exactly what I needed now. Thank you, Thank you.”

What Research Tells Us: The Challenges

“The majority of people entering or preparing for post-secondary education, 15-24 year olds, are more likely to experience mental illness than any other age group”2

According to a recent National survey (Ogrodniczuk, 2021) post-secondary students in Canada are experiencing high rates of:

- being overwhelmed and exhausted (95%)

- anxiety (83.7%)

- depression (81%)

- loneliness (81%).

The study further found that nearly three quarters of the students reported that “stress, anxiety, depression and sleep” had a negative impact on their academic performance (pg.839). Most alarmingly, the study found that one quarter of students experience suicidal ideation and 5% had attempted suicide. KPU’s Student Satisfaction Survey (2023) identifies similar issues with our students. Approximately 60% of domestic students and 50% of international students report moderate to very low scores regarding mental health well-being.

Research clearly states that neurodiverse people continue to face barriers and challenges on post- secondary campuses (Madriaga, 2010; Dwyer, 2023; Goddard, 2020; Roberts and Webster, 2020). Roberts and Webster (2020) and Walton and McMullin (2021) maintain that neurodiverse students are often overwhelmed in post-secondary settings and institutions should apply an inclusive approach to designing programs and spaces.

What the Research Tells Us: The Solutions

Low/reduced sensory spaces can provide a safe and supportive place to shelter from the ‘overwhelming environment’ (Colette and Colvin, 2013; Austin, 2019). The Washington Post (2020) lists the benefits of low/reduced sensory spaces on post-secondary campuses:

- Modulate the environment so that you can reduce the opportunity for over-stimulation.

- Creates a safe space with tools students can use to self regulate and manage anger, over-stimulation and stress.

- You can create a controlled space to assess the type of environment a student is most comfortable in and the sensory activities a person is most responsive to.

- You can create a comfortable space for students to relax in to

- help them interact with others.

- Provide a safe crisis and de-escalation area.

Reduce Stress

- Reduce Stereotyped/repetitive Behaviors

- Reduce Aggression

- Increase focus

- Motivate Learning

- Increase interaction

- Assist with sensory integration therapy”4

Low/reduced sensory rooms, or “Snoezelen rooms” meaning “to seek out or explore and relax” (Austin, 2019, pg.18) are spaces that are used to support self-regulation and de-escalation and reduced anxiety (Costa et a., 2006; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, 2016; Hastwell et al., 2017; Seckman et al., 2017). Typically, trained facilitators are present in the room there not to direct activity but there to provide direct or indirect support depending on the need of the user (Brown and Dunn, 2002; Austin, 2019).

Low/reduced sensory rooms were originally developed in the 1970s to support de-escalation for people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and learning disabilities in institutionalized settings (Long and Haig, 1992; Smith & Jones, 2014).

The use of low sensory spaces has also been incorporated into psychiatric settings and numerous studies have identified the space helped reduced psychiatric crisis and the need for restraint and seclusion (MacDaniel, 2009; Cummings, 2010; Sutton, et al., 2013; Smith & Jones, 2014; Bowman and Jones, 2016; Wigglesworth & Farnworth, 2016; Adams-Leask et al., 2018; Oostermeijer et al., 2021).

There are a few examples of universities providing permanent low/reduced spaces on their campuses. For example, Charles Darwin University in Australia provides a low/reduced sensory space to all students:

“The room is designed for students living with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, sensory disorders, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, mental health conditions, anxiety, or depression, or those needing some time out5”

Both Adelphi University and Stony Brook University in New York and the University of Minnesota at Duluth have added low-reduced sensory spaces to their campuses. The University of Saskatchewan has also created a low-sensory study space in the Murray Library (2023)6.

Austin (2019) concludes that providing low reduced sensory spaces can help post-secondary institutes address mental health challenges of students. Austin concludes that investing in low/reduced sensory spaces could “influence students’ decisions” about what institution they should apply to and states:

“Successful education of people with mental health issues is also critical to the economy and meeting AODA [Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act] objectives” (Austin, pg.22).

We can certainly add neurodiverse students and the Accessible British Columbia Act (ABCA) to this statement. Numerous studies (Madriaga, 2010; Cai & Richdale, 2016; Anderson et. Al., 2018; Gurbuz et al., 2018; Walton & McMillin, 2021) identify the many barriers neurodiverse students may experience on campus including “spaces that are loud, have poor acoustics, or are chaotic in noise, visuals, and activity” (Walton & McMillin, 2021: 84).

These barriers can have negative impact on academic performance and can further “increase stress due to sensory overload” (Van Hees et al., 2015. As quoted in Watson and McMillin: 84).

Low/reduced spaces are important measures in supporting neurodiverse students as well as the many students experiencing mental health issues. Providing a low/reduced sensory space is beneficial to all students and employees.

Further, providing low/reduced sensory spaces on campus will also help facilitate several recommendations from KPU’s Accessibility Plan (2023) including the following goal:

D3 Goal: We Will Advance Equity, Diversity, Inclusion Accessibility across KPU:

- Create quiet spaces on all campuses and comfortable rooms for resting and to support our neurodivergent population and individuals with disabilities.

- Maintain collaborations and relationships with disability justice organizations and encourage the development of new ones1.

Immediate Recommendations

- I recommend that KPU continue to offer the low/reduced sensory space on the Surrey campus during each exam period and high stress period.

These barriers can have negative impact on academic performance and can further “increase stress due to sensory overload” (Van Hees et al., 2015. As quoted in Watson and McMillin: 84).

Low/reduced spaces are important measures in supporting neurodiverse students as well as the many students experiencing mental health issues. Providing a low/reduced sensory space is beneficial to all students and employees.

Further, providing low/reduced sensory spaces on campus will also help facilitate several recommendations from KPU’s Accessibility Plan (2023) including the following goal:

Immediate Recommendations

- I recommend that KPU continue to offer the low/reduced sensory space on the Surrey campus during each exam period and high stress period.

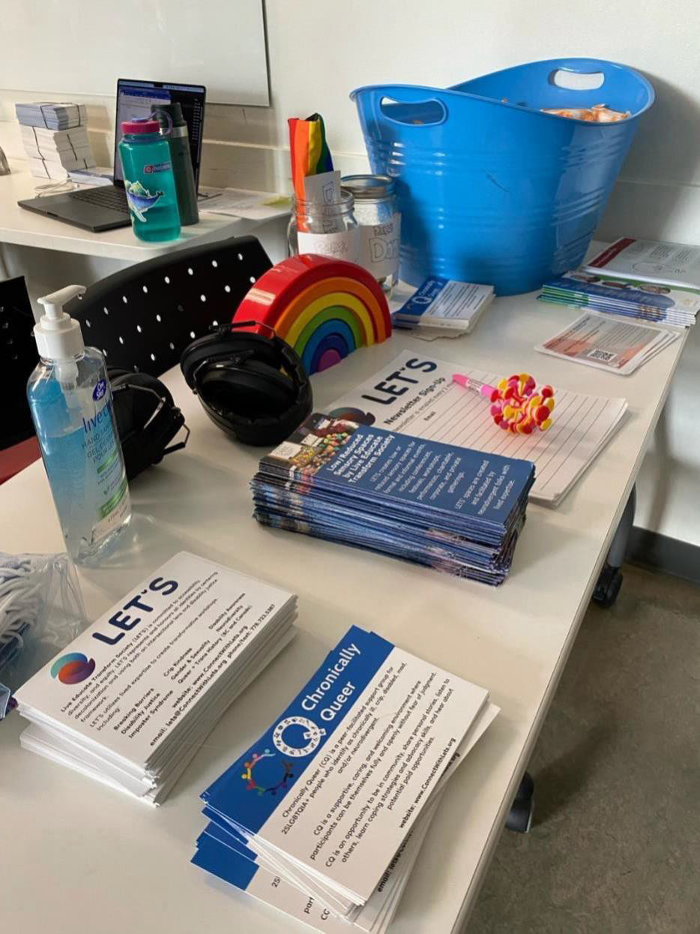

2. Continue to hire LETS to facilitate the low/reduced sensory space. LET’s staff are neurodiverse and from the 2SLQGBTA+ communities. They provide expertise and lived experience in supporting all students. The services they provided include the following:

1 on 1 event coordination.

- Trained, neurodivergent sensory space facilitators.

- A large assortment of stuffies, colouring books, crayons/ markers/pencil crayons, books, word games and reading materials.

- Stim toys for onsite use (used to regulate emotions and help with under or overwhelm).

- Selection of stim toys that event attendees can take home.Resource materials on social justice topics (such as 2SLGBTQIA+ disability

- Additional staff as needed1.

It is advisable to use the same room, Cedar 1015. This room has flexible space, lighting, and furniture.

Longer Term Recommendation:

- Provide low/reduced sensory spaces on all campuses.

- Have specific rooms designated as low/reduced sensory spaces.

References

Adams-Leask, Karen; Varona, Lisa; Charu, Dua; Baldock, Michael; Gerace, Adam; Muir- Cochrane; Eimear (2018). The benefits of sensory modulation on levels of distress for consumers in a mental health emergency setting. In, Australasian Psychiatry 2018, Vol 26(5) 514–519

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2018). Perspectives of university students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 651-665. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3257-3

Austin, Amanda. (2019). Addressing the Mental Health Challenges of Post-Secondary Education Students through the Implementation of Multi-Sensory Environments. Toronto: OCAD: Master of Design. In, INCLUSIVE DESIGN.

Bowman S and Jones R. Sensory interventions for psychiatric crisis in emergency departments – a new paradigm. Journal of Psychiatry Mental Health 2016; 1: 1–7.

Cai, R. Y., & Richdale, A. L. (2016). Educational experiences and needs of higher education students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 31-41. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2535-1

Champagne T. Sensory modulation and environment: essential elements of occupation. 3rd ed. Sydney: Pearson Clinical and Talent Assessment, 2011.

Cole KL. Sensory Sensitivities of Young Adults with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Explorations. 2015:80.

Colette M. Taylor and Kathryn L. Colvin. (2013). Universal Design: A Tool to Help College Students With Asperger’s Syndrome Engage on Campus. ABOUT CAMPUS / JULY–AUGUST 2013. Pp.9-20).

Costa, D.M., Morra, J., Soloman, D., Sabino, M. & Call, K. (2006). Sensory-Based Treatment for Adults with Psychiatric Disorders, OT Practice. 6 (3), 19-23.

Crane L, Goddard L, Pring L. Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2009 May;13(3):215-28.

Cummings KS, Grandfield SA, Coldwell CM (2010). Caring with comfort rooms. Reducing seclusion and restraint use in psychiatric facilities. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 48(6): 26–30. DOI:10.3928/02793695-20100303-02.

Dwyer, Patrick; Mineo, Erica; Mifsud, Kristin; Lindholm, Chris; Gurba, Ava; Waisman, T.C (2023). Building Neurodiversity-Inclusive Postsecondary Campuses: Recommendations for Leaders in Higher Education. In, Autism in Adulthood (pp. 1-14). Volume 5, Number 1.

Goddard H, Cook A. ‘‘I spent most of freshers in my room’’—A qualitative study of the social experiences of university students on the autistic spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05125-2.

Gurbuz, E., Hanley, M., & Riby, D. M. (2019). University students with autism: The social and academic experiences of university in the UK. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 617-631. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3741-4

Hastwell J, Martin N, Baron-Cohen S, Harding J. (2017). Reflections on a university based social group for students with Asperger syndrome. Good Autism Practice (GAP). May 9;18(1):97-105.

Long, A.P. & Haig L (1992). How do Clients Benefit from Snoezelen? An Exploratory Study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55 (3), 103-106.

MacDaniel M. (2009). Comfort Rooms: A Preventative Tool Used to Reduce the Use of Restraint and Seclusion in Facilities that Serve Individuals with Mental Illness. NY, USA: New York State Office of Mental Health.

Madriaga M. (2010). ‘‘I avoid pubs and the student union like the plague’’: Students with Asperger syndrome and their negotiation of university spaces. Child Geogr. 8(1):

39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280903500166.

Murray Library. https://library.usask.ca/news/2023/Update-on-low-sensory-study-space-in-the-Murray- Library.php

Ogrodniczuk, J.S., Kealy, D. Laverdière, O. (2021). Who is coming through the door? A national survey of self-reported problems among post-secondary school students who have attended campus mental health services in Canada. In, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research; Volume 21, Issue 4:837–845.

Oostermeijer S, Brasier C, Harvey C, et al. (2021). Design features that reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health facilities: a rapid systematic review. BMJ Open.

Roberts, J., & Webster, A. (2020). Including Students with Autism in Schools: A Whole School Approach to Improve Outcomes for Students With Autism. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(7), 701–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1712622

Seckman, A, Paun, O, Heipp, B, Van Stee, M, Keels-Lowe, V, Beel, F, Spoon, C, Fogg, L. Delaney, K.R. (2017). Evaluation of the use of a sensory room on an adolescent inpatient unit and its impact on restraint and seclusion. In, J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs;30:90–97.

Smith, S. & Jones, J. C. (2014). Use of a Sensory Room on an Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(5), pp. 22-30. doi: 10.3928/02793695- 20131126-06

Sutton D, Wilson M, Van Kessel K, et al. Optimizing arousal to manage aggression: a pilot study of sensory modulation. Int Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2013; 22: 500–511.

Sophie Wiglesworth* & Louise Farnworth. (2016). An Exploration of the Use of a Sensory Room in a Forensic Mental Health Setting: Staff and Patient Perspectives. Occup. Ther. Int. 23 (2016) 255–264.

Van Hees, V., Moyson, T., & Roeyers, H. (2015). Higher education experiences of students with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges, benefits and support needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1673-1688. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2324-2

Walton, Kerry R. McMullin, Rachel. (2021). Welcoming Autistic Students to Academic Libraries through Innovative Space Utilization. Pennsylvania Libraries: Research & Practice. Vol. 9, No. 2.

Weintraub, Karen. (2020). Room with an ‘ahh’: Colleges are giving students their own space to decompress. In, Washington Post, February 1 https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/room-with-an-ahh-colleges-are-giving- students-their-own-space-to-decom

Appendix A