Teaching Models

What the research says

Numerous studies reveal the positive effects of inquiry-based learning, including at the university level. In an algebra course, students taught through IBL scored significantly higher (Khasawneh et al., 2023). In a psychology field research-based course learners heightened skills such as team building, designing and producing a research project, and addressing ambiguous situations (Gilardi & Lozza, 2009). In a nursing course, IBL was applied in tutorials that cultivated metacognitive skills and more active engagement (Theobald & Ramsbotham, 2019).

Inquiry-based learning has origins in science education, hence most literature focuses here, such as on science experiments and laboratory activities. However, inquiry-based learning is applicable in any discipline. In generating inquiry questions, English students can select an author, genre or piece of writing. Business students can select entrepreneurship, a management style, or public relations focus such as social media. Design students can select a particular product in terms of its history, development, sustainability, or marketing. Trades students can select a specific automotive, electrical, plumbing or welding problem. Entertainment Arts students can select a visual effects style or idea, or a particular game design.

However, like any form of teaching, implementing inquiry-based learning effectively requires thought and care. Students used to transmission-based learning may be unfamiliar with the level of autonomy and responsibility that goes along with IBL. In addition, students may carry misconceptions about what constitutes effective teaching. In a study by Deslauriers et al. (2019), one group of students in an introductory physics course was taught via lecture, and another through active learning. Although the active learning environment significantly benefited learners on all counts measured, the students taught this way felt they would have learned more in the lecture format. This suggests instructors may need to put effort into getting students on board with IBL.

Whoever is doing the talking is likely doing the learning.

Trevor MacKenzie

On the instructor-side, another study by Voet and De Wever (2019) surveyed 536 teachers and showed that academics often misperceive student ability to engage in critical and higher order thinking. One solution to help students embrace IBL is to better explain the nature of knowledge (e.g., how learning occurs, how we make meaning, how we can recognize and assess knowledge, objectivism/subjectivism; in other words, epistemology) and the way it is constructed.

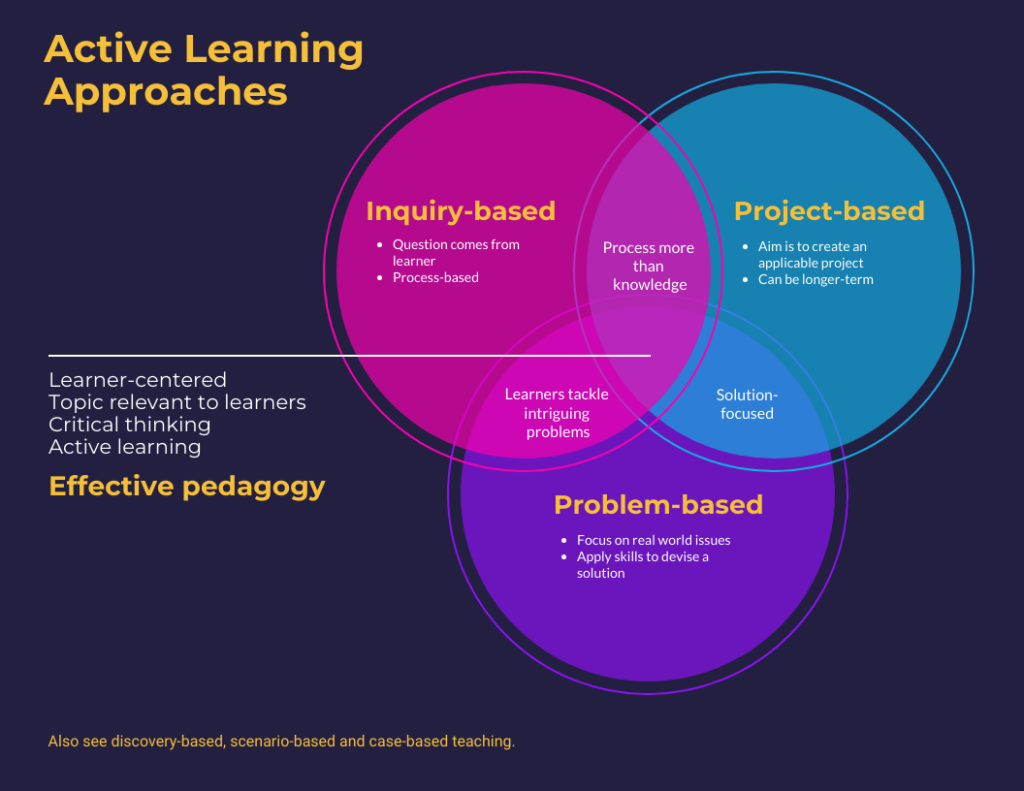

This Venn diagram illustrates the similarities among three active learning approaches. Project-based learning has students work in groups to solve a real-world issue and provide a clear solution often in collaboration with community. Problem-based learning also focuses on a real-world problem, but is shorter (one day or days instead of several weeks), less often multidisciplinary, and frequently uses case studies or fictional scenarios. Both can be argued to be different kinds of inquiry-based learning, however IBL makes clearer use of a guiding question and regular reflection.

Teaching Models Relevant to Inquiry Based Learning

All teaching models have their place in education. Many are connected to inquiry-based learning, or can complement this approach. The infographic below summarizes six teaching models, which are also described further below.

Experiential

learning is hands-on and connects experience with learning, and is a key aspect of constructivism upon which IBL is based. Similarly, active learning encourages participation with learners, such as through discussion and group work, which can facilitate the co-creation of the design, implementation, and assessment of student learning. Reflective learning is embedded throughout the phases of inquiry-based learning, enabling students to consider who they are as learners, what matters to them, where gaps exist in their knowledge, and how to carry their learning journey forward with awareness and intention. The learner-centered approach is a central feature of IBL, where the identity, interests and aims of the student become embedded in the learning process.

Lecture

can be an appropriate preamble to inquiry-based learning. Sometimes describing a concept is easier than facilitating a long activity. For instance, osmosis is an abstract physiological process that students often misunderstand. A short lecture on osmosis, including defining key terms, would be helpful before engaging in something more active, such as embodying this process, or checking understanding through clickers or one-minute papers, or an inquiry-based exercise where learners apply osmosis to something relevant to their lives (e.g., how to keep celery crunchy or designing IV drips). The flipped classroom incorporates the active elements of IBL, as students arrive having studied concepts pre-class. Class time is used to engage in interactive activities such as problem-based learning.

Teach the Teacher

An inquiry-based learning approach is a dramatic shift from lecture-based teaching. Thus a key step to incorporating IBL is preparing the teacher for this educational model. Common questions or concerns that may arise:

- “I wasn’t taught this way.” Inquiry-based learning may represent a way of teaching that differs from how you were taught. You may need to unpack assumptions around the role of teachers and students, how learning occurs, and the importance of authentic assessment.

- “I need training.” The skillset for transmission-based (e.g., lecture) teaching differs from that required to being a guide/mentor/facilitator. Important skills to learn for IBL include how to facilitate group process, building a safer/braver/accountable learning environment, letting the students lead, giving formative feedback, and encouraging and modeling reflective practice.

- “There isn’t time.” IBL often focuses on depth instead of breadth. This can be difficult to grasp for instructors that routinely teach as much content a 2-hour lecture affords. Instead of covering more topics, focus on fewer but more in-depth.

- “This is too big a change.” Like any significant shift, it can be helpful to start small. Instead of implementing a semester-long inquiry-based project, start with a short activity that includes elements of IBL. See the “Examples” section for some ideas. Or simply ask your students where they are at, and what or how they would like to learn. This sounds straightforward but is a clear path toward transformative learning.

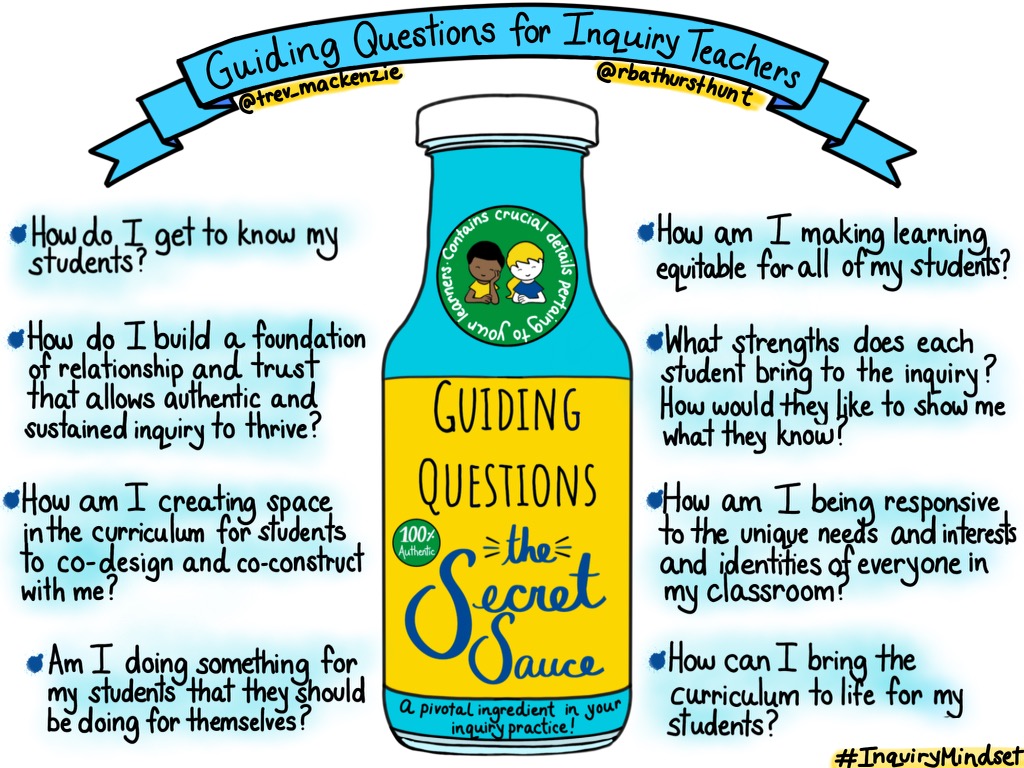

This image was developed by Trevor MacKenzie, author of Dive Into Inquiry and Inquiry Mindset. Although this image was originally created for younger learners, all questions are germane for post-secondary settings. In fact, many of these are too easily forgotten in university, such as the importance of getting to know your learners and being responsive to each unique group of students.

The phases of inquiry-based learning

Inquiry-based learning takes many forms. Breaking these into discrete steps runs the risk of discounting the cyclical and often non-linear nature of IBL. Therefore, use the following frameworks as inspiration rather than rigid structures. The basic outline for IBL includes an essential question for the learner, research that gathers evidence or data, analysis of this research, and the sharing of findings through a report, discussion, or presentation.

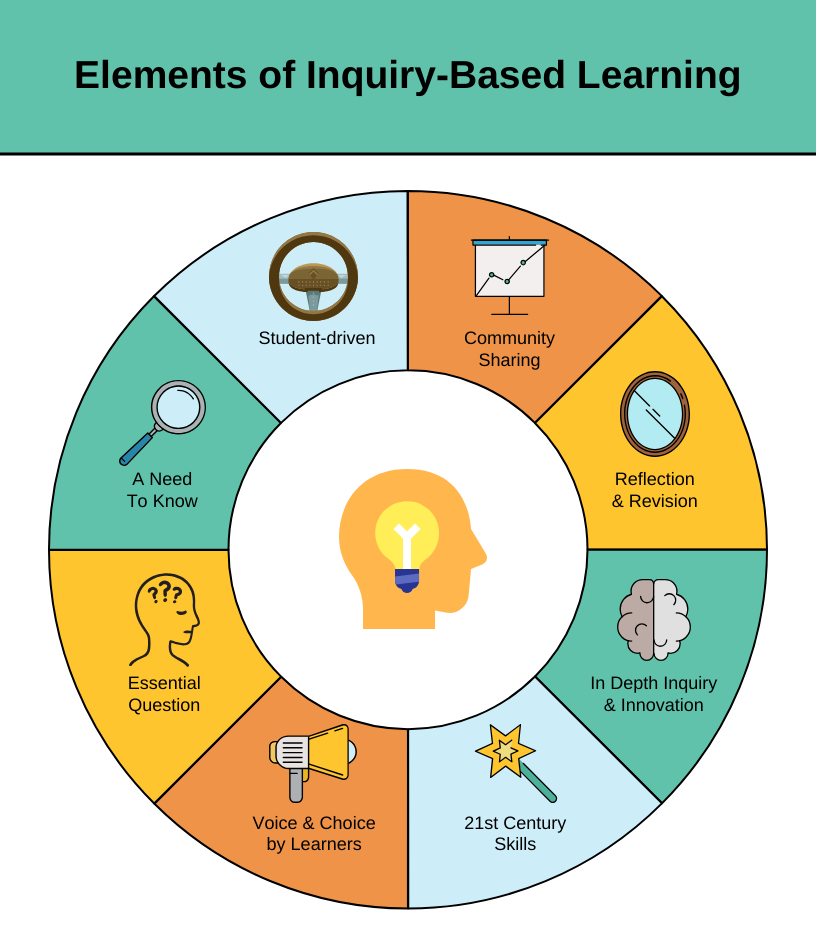

This image shows key components of inquiry-based learning and emphasizes its often cyclical nature. Learner inquiry usually begins with an essential question, not easily answerable (e.g., unGoogleable). This question directly connects to their interests and/or a real-world issue that is relevant to them. Students are in the driver’s seat, so they are integral in deciding what approach to take, resources to use, and the resultant solutions (with guidance and ongoing feedback provided by the instructor). Part of IBL is sharing your findings with the class or community, either through a presentation or other interactive event. Reflecting on the process should happen throughout, with students adapting their questions or process as needed. Students focus on a particular topic or problem in-depth, either during a single class or lab, or for entire semesters. This educational model employs and fosters 21st century skills, such as social skills, initiative, flexibility, communication, creativity, and collaboration. Through the IBL process, student voice is central and often leads the way.

Science-focused inquiry model

Pedaste et al. (2015) scrutinized 32 articles that described inquiry-based learning and developed the following framework, which places IBL into five distinct phases. It should be noted that this model retains a science/research focus. Other models (see “Inquiry Process” later in this section) are more open and applicable across the disciplines. If you teach in science and/or are looking for inquiry that relates directly to the scientific method, read on. If you teach in other areas, or are interested in broader frameworks of IBL, please skip this section.

Source: Fig. 3. Inquiry-based learning framework from Pedaste et al. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003 (Creative Commons license)

Watch video

Inquiry-based learning across (the science) disciplines

Alternate inquiry model: Inquiry Process

This alternate IBL model is adapted from the Inquiry Process developed by Trevor MacKenzie, a local educator and world-leading expert on inquiry-based learning. He highlights four pillars as part of this process: explore a passion, aim for a goal, delve into curiosities, and new challenge, all of which underscore the importance of learner choice and autonomy. Here are the six phases of the Inquiry Process:

The table outlines some of the key steps and considerations for inquiry-based learning in two broad fields of education and research. First, the natural sciences (biology, chemistry, earth sciences, physics, astronomy, mathematics and sometimes other disciplines such as psychology) where accuracy and repeatability of results are integral to the process. Second, the arts and humanities, which value qualitative research methods including arts-based, case studies, focus groups, narrative, ethnography, and more. Although this table stresses a linear methodology for inquiry-based learning, it should be noted that IBL can be cyclical, and less linear approaches often resonate better with the inquiry model. The intention for this table is to emphasize the applicability of the inquiry process across the disciplines.

| Natural Sciences | Arts & Humanities | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation, introduce topic, variables determined | Orientation, introduce topic or student finds their topic | In science, the scientific method may mimic the inquiry process. In Arts/Humanities, topics and methodologies can be more fluid. |

| Ask questions | Ask questions | An essential question is part of any inquiry, though how it is determined or expressed varies |

| Reflection and discussion | Reflection and discussion | Explore assumptions, biases, and personal feelings with self and others |

| Hypothesis generation, make predictions | Brainstorming, idea generation, refine focus | A hypothesis can be part of a scientific inquiry, though other science inquiries may focus on ideas outside the scope of the scientific method |

| Design experiment | Get clear on intentions | In science, experimental design is objective and controlled. In Arts/Humanities, subjectivity is a vital part of the process. |

| Conduct observations or experiments | Identify resources, collect evidence, explore through empirical, communal, or reflective practices | Empirical data is a part of any inquiry, highlighting the importance of direct observation/experience |

| Gather data | Gather evidence/experience | Quantitative data is more typical for science, but qualitative data—including journaling or creative expression—are equally valid in inquiry |

| Data interpretation | Synthesizing evidence/experience | In science, statistical analysis is common, whereas Arts/Humanities may focus on qualitative or personal experience |

| Devise explanations or mechanisms for patterns observed | Explain process, evaluate experience, and draw conclusions | Science often focuses on the underlying mechanics of how things work, Arts/Humanities may focus on social, economic, educational, or other aspects |

| Reflection and discussion (again, and throughout inquiry process) | Reflection and discussion (again, and throughout inquiry process) | Explore assumptions, biases, and personal feelings |

| Share and discuss | Share and discuss | Communicating the process and/or findings is a key step for any inquiry |

| Apply knowledge to new scenarios | Reflect on experience and apply this to future learning | Future thinking imagines next steps for this inquiry |

Common misconceptions and pitfalls

“Is inquiry-based learning rigorous?”

The short answer: yes. But this depends on how you define rigorous. If rigorous is defined as strict and difficult for the sake of being difficult, then this does not resonate with IBL. Nor does teaching more content or reaching toward a specific standard where all learners are expected to reach certain benchmarks at the same time. Conversely, if rigorous refers to challenging students to think and act in innovative ways, or to foster critical thinking and deep learning, then IBL offers a clear path to these goals.

“Does inquiry-based learning require more work for the instructor?”

Initially, yes. If you are not trained in the inquiry process, then this takes time to learn facilitation skills and active learning strategies. Similarly, providing formative assessment and regular feedback can take longer than summative assessment. However, the ability of IBL to increase learner motivation, deter plagiarism, and help students teach themselves (and their peers) may ultimately lessen our workload.

“Is it relevant for [insert your discipline here]?”

Yes, inquiry-based learning has applications across the curriculum. Although originally developed to mimic the scientific method, IBL is adaptable and relevant for any course in any discipline.

“Sure, I value skills development, but I need to teach the content.”

Fostering competency skills and learning content do not need to be mutually exclusive. Well-framed and supported inquiry-based learning can help students master content while at the same time cultivate learner independence, communications skills, and increase self-esteem.