Implementing

Inquiry-Based Learning

Preparing for Inquiry-Based Learning

Watch video

Getting started with inquiry-based learning

Ready to implement inquiry-based learning with your students? Here are four starting points.

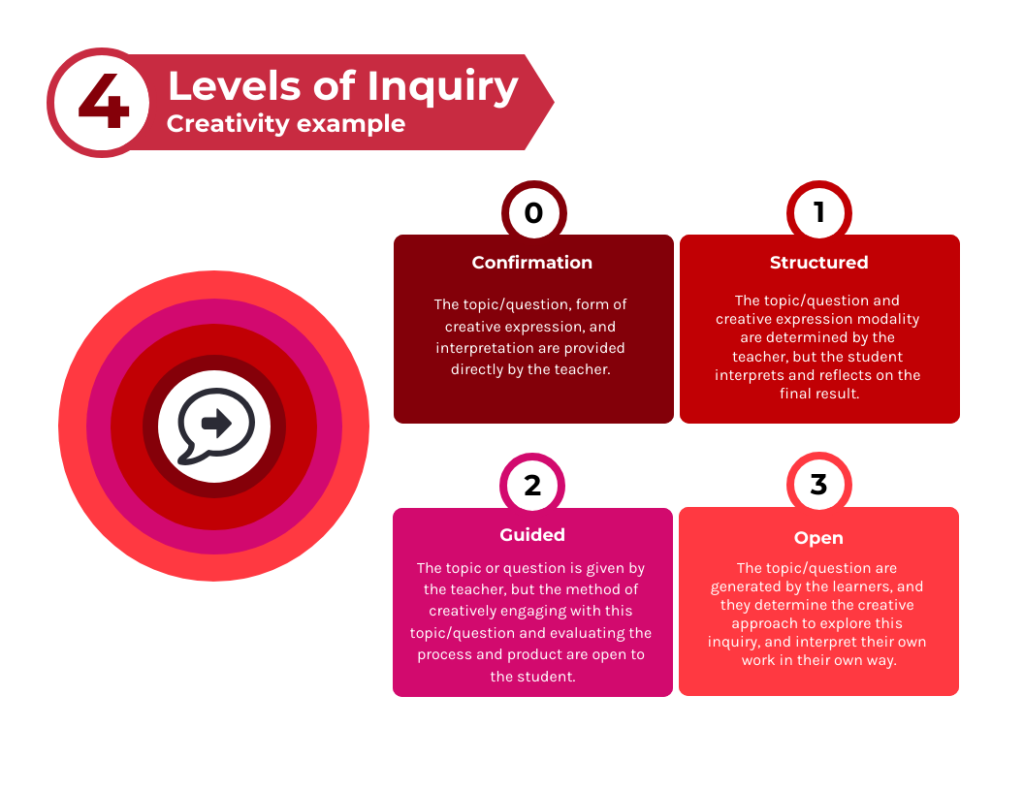

Levels of Inquiry

There are four levels of inquiry. Those newer to inquiry-based teaching may want to begin with ‘Structured.’

| Level of Inquiry | Source of question/topic | Approach or Methodology | Interpretation and Reflection | Sharing/presentation format |

| 0: Confirmation | Teacher | Teacher | Teacher | Teacher |

| 1: Structured | Teacher | Teacher | Student | Teacher/student |

| 2: Guided | Teacher | Student | Student | Teacher/student |

| 3: Open | Student | Student | Student | Student |

The above table outlines the four levels of inquiry, which varies from Level 0 (confirmation or verification) where learner self-direction is lowest and the direction from the instructor or provided resources are the highest. Conversely, Level 3 (open) maximizes learner autonomy and independence, with the role of the teacher focused less on providing answers and more on asking powerful questions and facilitating authentic learning and assessment.

A study (Blanchard et al., 2010) with 1,700 science students compared Level 0 (confirmation/verification) and Level 2 (guided) inquiry approaches. Level 2 guided inquiry resulted in better outcomes for test scores, long-term retention, and academic growth over time, especially when the teacher was comfortable and adept at facilitating inquiry-based learning. The Level 0 inquiry approach included explicit lab write-ups and worksheets, where findings were confirmed by the teacher. The Level 2 inquiry approach had no lab instructions or worksheets; instead, a question or scenario was provided for students to examine, as well as germane background information, and students developed their own hypotheses and methodologies.

The above image provides an example for students exploring creativity, such as in IDEA (Interdisciplinary Expressive Arts), as part of their inquiry. In Confirmation (Level 0), the teacher directs all aspects of the inquiry. In Open (Level 3) the learner is in the driver’s seat for the entire process, though still calls upon the teacher for help or guidance when needed.

Not all inquiry-based learning is the same. Although providing learners with some guidance is recommended, these can vary from structured IBL (e.g., providing a list of questions to choose from, clear steps to follow, a detailed rubric) to open or free inquiry (e.g., where learners develop all of these themselves). A number of factors will influence how you implement your inquiry-based learning with your students:

- Instructor experience and comfort level. If you are new to this you will likely want to start small with ‘confirmation’ or ‘structured’ IBL, and offer more specific guidance.

- Time available. Open inquiries require time for learners to develop their questions, frameworks, and methods. This if preferably done in-class in consultation with their fellow learners. If time is limited, you can try a shorter inquiry-based activity that occurs within a single class.

- Intention for this inquiry. What is it you hope to achieve through facilitating inquiry-based learning with your students? Helping them understand a tricky scientific concept, or having learners explore their identity and responsible citizenship in the world, or connecting creativity to personal growth are very different focuses, yet each is possible under the IBL model.

Factors that do not prevent inquiry-based learning:

Seven steps to start teaching through inquiry-based learning:

Think of a key course topic or theme that you want students to explore.

Determine the level of inquiry: confirmation, structured, guided, or open.

Come up with 2-3 powerful questions to ask students.

Provide a framework (e.g., timeline, project proposal template, list of materials, list of where to look for resources, checklist, etc.) to help anchor students. Show them artifacts or examples of inquiry-based learning.

Facilitate group discussion and experiential activities related to the IBL topic/theme.

Be clear on when (and how) you will provide formative feedback.

Determine how learners will share their inquiries. The best option may be simply to ask them how they want to express their learning. Can you also connect learners and/or their learning with your local community?

Those who are doing the assessing are doing the learning.

Trevor MacKenzie

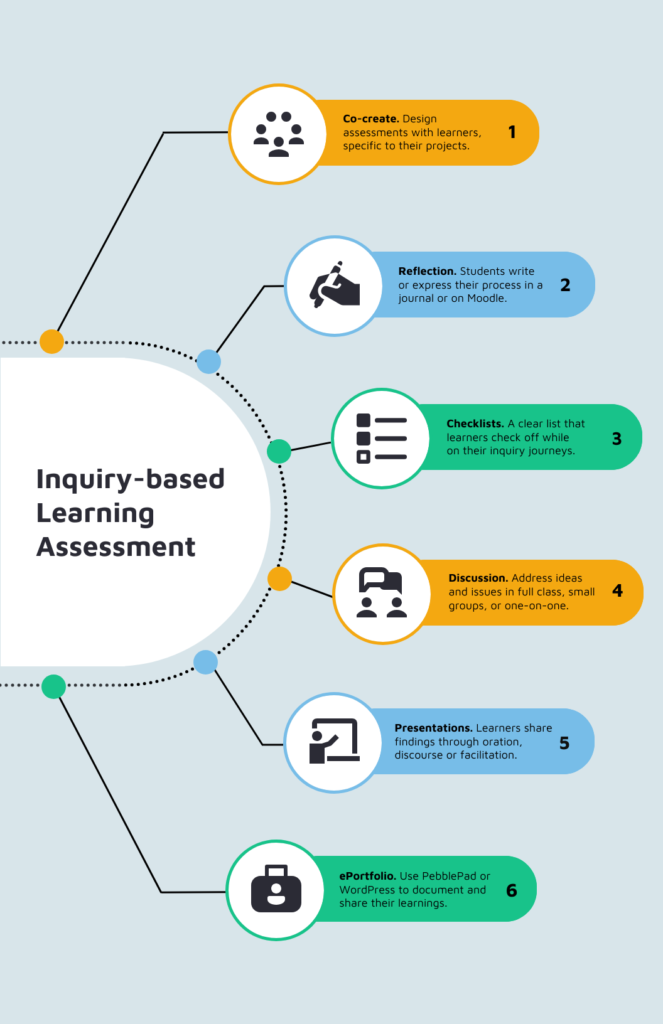

Assessment of Inquiry-based Learning

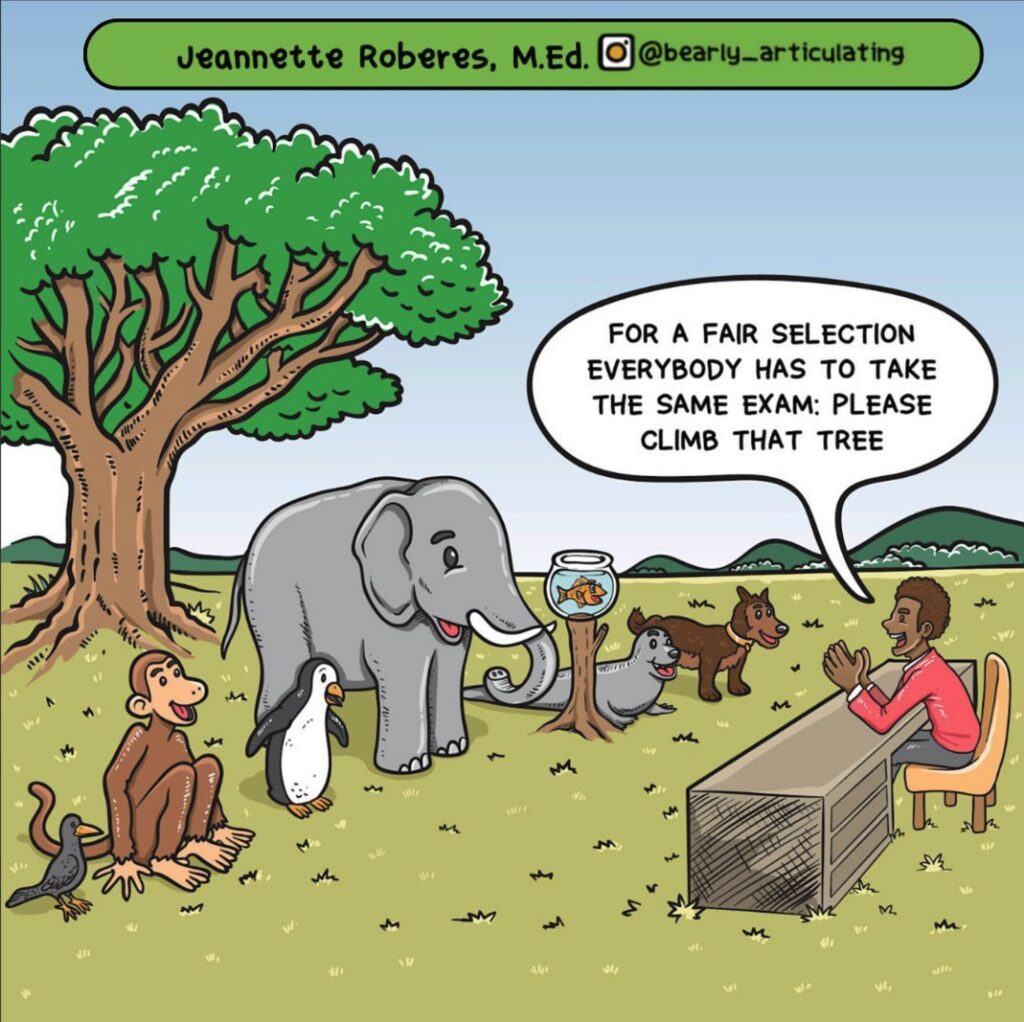

As this comic illustrates, not all learners are the same, and neither are all assessments. The most suitable assessment methods in inquiry-based learning are collaborative, reflective, and formative.

The above infographic offers six ways to develop assessment for, and formatively assess, inquiry-based learning. Summative assessment may be suitable for larger inquiries, keeping in mind that process is typically more relevant than the final product.

Formative assessment is not a task. Formative assessment is an ongoing, embedded practice that allows teachers to constantly make adjustments to their teaching based on what they’re observing. Feedback is a mindset.

Ron Ritchhart, Senior Research Associate at Harvard Project Zero

Powerful questions you can ask learners towards the end of their inquiries:

- What did you learn about yourself, others, and/or your community during this process?

- What challenges or obstacles did you face? Were you able to overcome them? Why or why not?

- How did/does this inquiry stretch you?

- How are you/did you interpret your data from your inquiry?

- Were you changed by this inquiry? Why or why not?

- What question(s) still remain? How might you address these?

- How is your inquiry connected to the land or natural world?

- What misconceptions did you discover during the inquiry process? What allowed you to discover these misconceptions, and how did you address these?

- How could/will you carry this inquiry into the future?