Foundational Theories

This section will delve into a range of fundamental theories and concepts that will shape the creation and implementation of learning outcomes across diverse post-secondary educational settings. Theories explored in this section include:

Outcome based education was popularized by William Spady; however, its roots stem back to the 70s with Mastery-Based Education and the works of Bloom and Carrol in the 60s. OBE was seen as an alternative to traditional education. At the time, traditional education was time-based and focused on the material that instructors felt was important to impart to their students. Instructors had a prescribed amount of time with which to present the material of their choice. The material presented would change from instructor to instructor and semester to semester. Gaining a precise understanding of a student’s learning within a study program was notably difficult, as was ensuring that two students who completed the same program possessed identical content knowledge and proficiency levels.

Outcome based education focuses on identifying what the student needs to learn to be successful and providing it in a flexible enough manner to engage students with different learning preferences. Outcome based education has three key principles: Student-Centered, Clarity, and Flexibility (Spady, 1994).

Student-centered means the focus of the educational activity is on the students learning rather than on the instructor’s teaching. This means all aspects of the educational activity including the lesson plan, instruction, and assessment are all tied to “what the student learned” rather than “what was taught”.

Clarity comes from the articulation of learning goals and the articulated demonstration of these goals in advance of the educational activity. The clarity supports all participants involved in the learning activity. The students have clarity around what is expected of them, new instructors have clarity around the material they will be teaching, administrators understand what is transpiring in their institutions, and employers have clarity around the expected knowledge, skills, and attitudes of graduates from a particular program.

Flexibility is enhanced by student-centered focus. Since the intention, delivery, and assessment of the lesson is focused on what the student has learned, then the educational activity is only over after the student has learned the content. If an instructional approach is used during an educational activity and the student does not learn the content, then the instructional approach is changed, and the content is presented again until the student successfully learns the content.

These key principles suggest some assumptions around students and learning. The first of these is “all students can learn and succeed, but not on the same day in the same way” (Spady, 1994, p.10). If we accept this assumption it becomes clear that educators need to employ a dynamic approach with their learners. Delivering a 2-hour lecture and expecting it to be equally effective for every student every day is misguided.

“Successful learning promotes even more successful learning” (Spady, 1994, p. 9). The current material the student is learning is necessarily situated on a foundation built on previous learnings. Similarly, the current material the student is learning will be situated as a foundation for subsequent learning. Accepting this assumption helps recognize that learning is dynamic; It both impacts and is impacted by other learnings. For an instructor to plan a successful educational activity, they must have some insight into the learning foundations present in their current students.

“Schools [Institutions] control the conditions that directly affect successful school [institutional] learning” (Spady, 1994, p. 9). The accountability for learning rests with both the learner and the educator. The educator can make changes to the environment, the planning, the practice, the delivery, and the assessment of learning to maximize the success for the learner.

These principles and assumptions provide some insight into the intention and high-level value of learning outcomes and outcome-based education. This resource will now spend some time exploring the value and relevance of outcomes through an educator’s lens.

If we were to consider the process of education in an Outcome Based Education manner, it might look like this.

Steps one through three articulate the learning outcome, steps four, six, seven and eight refer to the development of assessments and step five speaks of the delivery of instruction. These three components, outcome, assessment and instruction, represent the three components required to achieve constructive alignment and curriculum.

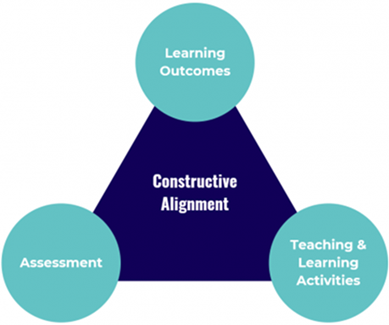

John Biggs further develops concepts associated with outcomes-based education, shaping them into a framework referred to as constructive alignment (Biggs, 1999, p. 64). This framework delineates three essential elements. These key elements are:

- Intended learning outcome – A demonstratable goal of the learning activity. What the student will be able to do, know or feel as a result of the lesson, course, program, etc.

- Planned learning activity – The format and method for delivering the educational material that will lead to the student meeting the planned and communicated outcome.

- Planned assessment – The format and type of assessment to determine that the learning articulated in the goal has been achieved.

Biggs felt that these three components influenced and were influenced by each of the other components. More importantly, each of these components needs to align with the other components.

By this, Biggs meant that the learning activity should be deliberately designed to support the student in achieving the intended learning outcome, that is the learning goal and how it is demonstrated, and the assessment should be deliberately designed to measure the demonstrated achievement of the goal.

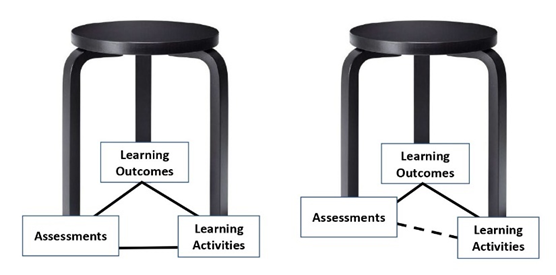

Think of constructive alignment as a stool with three legs. If one of the legs on the stool is shorter than the other (misaligned), it cannot be used for its intended purpose.

Learning outcomes, assessments and learning activities are constructively aligned. Metaphorically, all three legs of the stool are of equal length.

Learning outcomes, assessments and learning activities are not constructively aligned. Metaphorically, notice the assessments of the leg of the stool is shorter than the other.

The strengths of this method lie in its intentional design, which involves delineating objectives, specifying assessments for those objectives, and creating activities that facilitate the attainment of those objectives. In this way, it comes much closer to achieving the instructor’s vision of student ability and their demonstration of that ability. Contrast this with a traditional learning approach.

In a traditional learning approach, the steps are usually:

- Identify a topic or content to be covered.

- Plan a sequence of educational experiences to convey this topic.

- Create an assessment to measure the learning that should have taken place.

In this traditional approach, the content may relate to the topic, and it may not be selected to meet a student’s learning goal. That is, it may support the instructor’s interests and it may not support the student’s needs. The educational activities are more focused on delivering the content rather than supporting the student in achieving their learning goals. The lecture is often the choice for delivering content and is the least engaging instructional approach with the lowest student retention and recall. Finally, the assessment is designed to measure the content delivered in the teaching rather than measure the students learning. The assessment will likely be weighted to the content delivered around the time of the assessment’s design and focus on rote memorization rather than understanding or demonstration of learning. This traditional approach often leads to a scenario where the instructor is asking the student to report back to the instructor about what the instructor told the student. This often results in a lack of durable transferable learning and leads to poor student engagement.

In contrast, the backward design approach, the steps are as follows:

- Identify the learning goal and how that goal will be demonstrated.

- Design an assessment that measures the demonstration of the learning goal.

- Plan a sequence of educational activities that will prepare students to successfully complete the assessment.

These steps put the students learning at the forefront of the educational activity. The learning goal is about what will be learned and demonstrated, not what content will be delivered. The assessment is designed to measure the achievement of this learning goal and its demonstration. It is directly relevant to the learning goal, student-focused, and has nothing to do with measuring the delivery of content. Finally, a sequence of educational activities is planned to support the student in successfully completing the assessment. The instructional activities are directly related to the assessment of the learning goal and supporting the student. As the focus is on student learning, all the components of the educational activity are directly focused on the student. This increases the likelihood that the student is engaged in their own education. Moreover, if the student lacks engagement this approach encourages the instructor to try something different to improve engagement. Students who are engaged in their own education have higher rates of retention and recall. Instructors may still use lecture for some educational activities and if lecture is not effective in supporting students to achieve the intended Learning Outcome, this will be abundantly evident based on student performance on the assessment, this will allow the instructor to adjust their instructional activities moving forward.

While it is possible instructors to design and deliver an effective lesson without using backward design, following this process will make it easier to regularly achieve effective educational design.

This is not the same thing as “teaching to the test”. “Teaching to the test” involves educational activities that are heavily focused on preparing students for performance on a standardized test. Activities often include rote memorization practices, drills, and a lack of understanding of the subject matter. Students subjected to “teaching to the test” practices often perform well on multiple-choice quizzes and are unable to demonstrate or express their learning in any other way.

With backward design the instructor acts as a subject matter expert, designing the outcome. The outcome may require memorization, it may require synthesis and application of a concept to a situation or anything in between. The assessment is designed to measure the students’ performance of the intended Learning Outcome. That assessment may be designed to measure a student’s memorization ability, their performance on a complex task, or their beliefs and values around sociocultural occurrences. The instructor is then able to choose the educational activities they feel will best support the student in a successful performance on the assessment. In “teaching to the test”, the instructor is restricted from teaching well. The content is predetermined the assessment is predetermined and the instructional activities are predetermined. In backward design, the instructor is seen as the subject matter expert who establishes the intended Learning Outcomes, the assessment, and the instructional activities. In backward design, the instructor is empowered to support the student in achieving the intended Learning Outcomes developed by the subject matter expert.