A Year of Intended Collaboration

Many a New Year’s Eve I have seen, and many a New Year’s Eve I have sworn, resolute that I would do this, or that, to better myself. I would pledge away my sweet tooth, declare limitations on my merlot, promise to temper my social media use, or various other pettifogging deprivations.

This ritual was always well-intended. As someone who believes in the never-ending pursuit of personal and professional growth and development, I would like to think that I take action to become a better human each year. Nevertheless, the formality of petty resolutions declared on an annually set date that I would inevitably fail to achieve, became less palatable over time. Thus, years ago, I gave up the seemingly pointless tradition. I was not alone, as resolution makers have long histories failing in their habit-changing goals. Norcross and Vangarelli (1988) longitudinally studied 200 participants who attempted self-change through declared resolutions and found that a mere 19% maintained them at the two-year marker. Various other studies in recent years have yielded similar findings (Hawkes, 2016; McManus, 2004; Mukhopadhyay and Johar, 2015). Therefore, it made sense to tuck away my inner resolution maker.

Flash forward to September 2021 at our semester start departmental kick-off meeting, where my inner resolution maker, who long lay dormant, resurfaced.

It could have been the excitement of a new semester and new team members; it could have been that my energy levels were at their peak after a rested vacation; whatever the reason, the resolutionphile (sic) within me attended that meeting. Consequently, when Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani kicked off the session with an opportunity to share our wishes for the school year, I made a bold declaration:

“I am excited to work with all of you, and on that note, I would like to announce my intention to personally work with each of you at least once this school year.”

Whether it was a moment of madness or a spike in endorphins, I was now self-committed to collaborating across contexts, across working schedules, across “knowledge boundaries” (Edmondson and Harvey, 2018, p.347).

Within the Teaching and Learning Commons (TL Commons) structure, various roles work asynchronously, often with no intersecting duties, to support institutional goals, so this would be no easy feat. Nevertheless, I was encouraged by literature that emphasized the value of collaboration across contexts (Bratton & Tumin, 2012; Edmondson & Harvey, 2018; Montanari et al., 2020), and so I shelved my doubt and set out on a year of intended collaboration.

And Intention might be the key to success. Montanari et al. (2020) considered that individuals drive the evolution of how collaborations unfold; they must desire to collaborate with others. Desire to collaborate, check! To encourage me even further, Edmondson and Harvey (2018) contended that working in teams with diverse surface-level attributes like gender and age, coupled with deep-level attributes like functional or educational background, could positively impact the development of innovative solutions (p. 347). And the humans of the commons are undoubtedly diverse, with 22 people respectively working in one of the following capacities: (1) leadership, (2) administrative support staff, (3) learning technology, (4) open education, and (5) educational consultants. Moreover, the team is of assorted ages, genders, and educational backgrounds. Diverse team, double check!

I do have many opportunities within my department to partner and collaborate with my team members, and I am grateful for that. But as we grow as a teaching and learning centre and add new team members, we often find those opportunities with those in similar roles or familiar histories. We remain within our “knowledge boundaries” (Edmondson and Harvey, 2018), and see little reason to cross those invented lines that separate us in so many ways. Arguably, the institution would benefit if we did. Ingunn and Gunn (2014) argued that creative collaborations could spur innovation (p. 546). People, humans, diversity; power in cross-context collaborations.

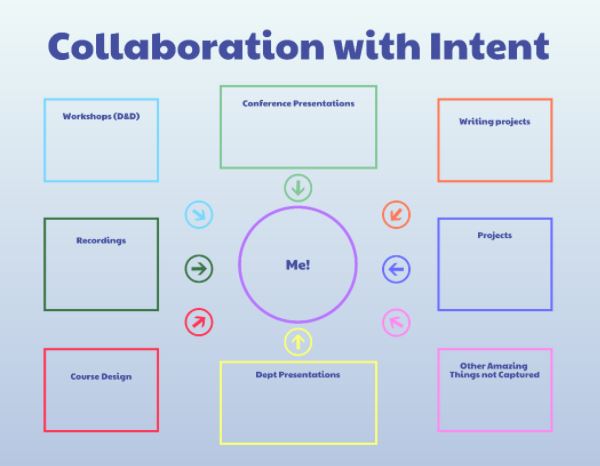

As I embarked on this exercise, I knew I would need a system to track my work and reflect on this experience at the end of the school year. These collaborations would still need to remain within my scope of work, within the scope of the work of my fellow collaborators, and the scope of the TL Commons’ objective of supporting KPU’s broader strategic plans for teaching and learning. Figure 1 depicts the seven types of collaboration I anticipated engaging in, namely, (1) conference presentations, (2) writing projects & other projects, (3) recordings, (4) course design, (5) department presentations, (6) the design and delivery of workshops, and (7) other amazing things not captured. These buckets would serve to organize and focus my journey and offer a method of collecting and reflecting on these shared experiences and accomplishments. At the end of the year, I hope this results in a visual representation of how collaboration “looked”, and where it could grow.

Since the September meeting, I have been grateful to collaborate with people I might not have, before this ambition. These collaborations resulted in products and ideas that will benefit our department and institution but have additionally had the positive side effect of learning more about my colleagues. A recent collaboration to create a video resource included team members across three roles. We discovered that one of the team members had a passion for professional makeup; what a fantastic addition to our video project! The makeup chair became a hub of activity as we took turns in the studio, telling stories and sharing insights about one another as we laughed, reflected, and united; across those “knowledge boundaries” (Edmondson and Harvey, 2018, p. 347), to learn and grow. The video was a success; it showcases the Foundations in Teaching Excellence modules developed to support the design and delivery of exceptional learning experiences at KPU, and I am proud of that. Nonetheless, I am also proud of the bloopers, the silly chatter, and the opportunity to learn a little more about one another; the humans of the commons.

The past few months of intended collaboration have reinforced the value of focusing on growth practices rather than attempted self-change through deprivation (ha! take that inner resolution maker). I still plan to collaborate with everyone in my department, and I have many more partnerships needed to reach my goal in April (stay tuned, because if we haven’t had a chance to work together yet, I will reach out!). My intention is creating new opportunities for collaborations, which is what I had hoped for. What I didn’t intend to happen are the positive side effects of these collaborations, the new relationships, the new appreciations for my colleagues as whole humans, and the unexpected learnings that come when we take the time to listen and work together. I feel that I have already begun to reap the rewards of these new collaborations and I am only in semester one.

One semester down and two to go – destination collaboration is in sight! At least that is my Intention; what is yours?

Figure 1

Collaboration with Intent

Note. Seven themes of focus for intended collaboration 2021-2022 (Gedak, 2021)

References

Bratton, W., & Tumin, Z. (2012). Collaborate or Perish!: Reaching Across Boundaries in a Networked World. Crown.

Edmondson, A. C., & Harvey, J.-F. (2018). Cross-boundary teaming for innovation: Integrating research on teams and knowledge in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 14.

Hawkes, N. (2016). Sixty seconds on… New Year resolutions.

Ingunn, J., & Gunn, E. (2014). The Room of Opportunity: Understanding phases of creative knowledge processes in innovation. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26(8), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-10-2013-0077

McManus, C. (2004). New Year’s resolutions. BMJ, 329(7480), 1413–1414. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1413

Mukhopadhyay, A., & Johar, G. V. (2005). Where There Is a Will, Is There a Way? Effects of Lay Theories of Self-Control on Setting and Keeping Resolutions. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1086/426611

Montanari, F., Mattarelli, E., & Scapolan, A. C. (Eds.). (2020). Collaborative Spaces at Work: Innovation, Creativity and Relations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429329425

Norcross, J. C., & Vangarelli, D. J. (1988). The resolution solution: Longitudinal examination of New Year’s change attempts. Journal of Substance Abuse, 1(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-3289(88)80016-6

Lisa Gedak

As one of KPU's Teaching & Learning Strategists, Lisa supports faculty through various methods, including workshops, webinars, and individual and group consultations. She is passionate about instructional design, the intersection of pedagogy and technology, and philosophical approaches supporting learner-centred education. Lisa has her Master's in Learning and Technology (MALAT).