Who comes first in the ‘new normal’ of pandemic pedagogy? The teacher or the learner?

As trending hashtags and commercial taglines keep reminding us, the answer is neither, for we are in this together. If ever there was a time to yank the sage off the stage and extend a hand as a guide on the side, it is now.

As we all suffer collective whiplash from the sudden pivot to remote learning, it is imperative that we remember that it is not just our heads that continue to spin trying to adjust to ‘the new normal’ of pandemic pedagogy, but our students’ as well.

In fact, results of surveys conducted this summer put faculty only slightly ahead of students when it comes to experience with online learning. According to results from a BC Campus survey of post-secondary educators in June 2020, “63 per cent of respondents had never taught online before the pivot.” (Caldwell, 2020). For learners, data from KPUs Summer 2020 Remote Learning Survey Report, revealed that more than 70% of students had never engaged in remote learning, including online classes, before the pandemic (Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 2020). So, while the learning curve for both faculty and students appear to be steep, faculty need to take the lead and navigate students through, what is for many, unchartered territory.

Do not assume that because your students are tech savvy that they have the necessary competencies to learn online. Even the pre-pandemic literature on student readiness for online learning reports that both faculty and students over-estimate student abilities to learn in an online environment (Kim, Hong, & Song, 2019; Parkes, Stein, & Reading, 2015) While many learners may have the technical competencies to navigate a virtual learning environment, they do not necessarily possess the academic competencies to complete the work. For instance, posting a comment to a friend’s social media page does not require the same level of writing or critical thinking skills as posting a well-argued, scholarly response to a discussion forum, nor does the cognitive load required to skim one’s newsfeed for information equate to what is needed to actively engage in reading academic texts.

Self-regulation and time management skills are also cited as significant challenges for those new to online learning, but also necessary for success (Martin 2020; Ejubović, & Puška, 2019; Parkes, Stein, & Reading, 2015). Splitting and managing one’s focus and time between academics, work and life is difficult enough without the added stressors associated with COVID.

So, how do we as faculty guide our students through a situation that we may not be fully confident navigating ourselves? To extend my hand as guide on the side, I offer up some strategies in solidarity with both faculty and students. They are yours to consider, try or adapt. They will likely not stop the spinning, but I hope they may slow it down a little.

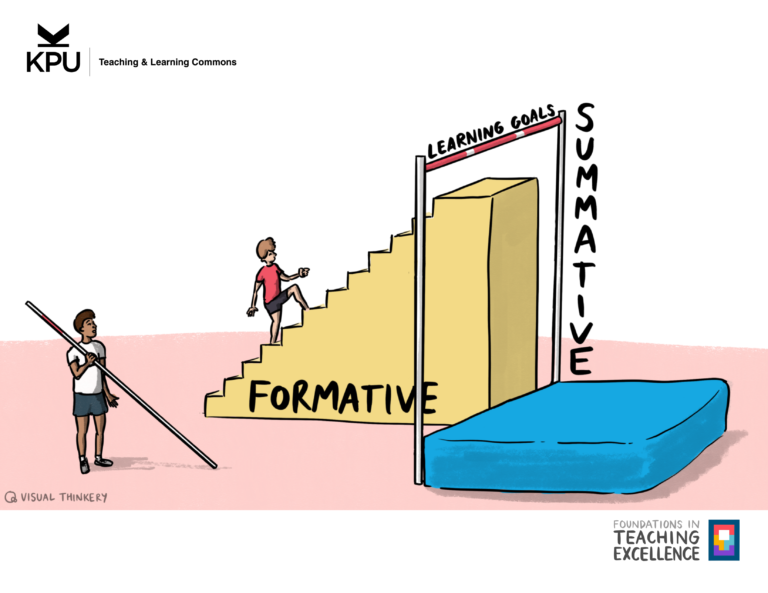

- Do not make assumptions about students’ technical and academic competencies. Survey your students during or before the first week of class to assess their experience with online learning. Inform students about and provide links to online learning and academic supports like KPU’s Learning Centres and Libraries. Provide practice activities to scaffold and assess technical and academic competencies, giving you both time to learn and adjust.

- Recognize your own needs for support. Be honest with your own comfort and competencies with online learning. Do what you can and give yourself the time to learn. Go slow and take it one step at a time. Get help when you need it, and take advantage of a variety of KPU faculty supports such as the Teaching and Learning Commons, The Learning Centres, the Library and other Faculty and Staff Online Services and Resources.

- Clearly communicate your expectations and instructions for learning activities. If you do not want emoji and LOL’s to appear in your students’ forum posts or emails, let them know. Provide clear activity instructions with links to learning outcomes, resources, and assessment criteria. Include step-by-step guides and/ or graphic workflows to guide students through more cognitively or technically complex activities. Doing so will help students self-regulate and manage their time.

- Reduce and focus cognitive load. Strip down your courses and focus on learning outcomes. Providing learning resources (i.e. readings, instructional videos) and activities in “very clear and well-structured, … manageable chunks, allow good opportunity for students to practice what must be learnt, and enable opportunities for the teacher to see students’ work and provide feedback (Martin, 2020, p. 1). Guiding students to focus in smaller chunks on what is important will improve self-regulation and time management. Further reduce distractions by organizing your course site in a clear structure that is easy to navigate.

- Build community, engagement, and accountability. Establish a clear and regular online presence. Communicate regularly with students via email, announcements, and feedback. Monitor student activity and check in with students who seem to be struggling. Inform students about and provide links to non-academic supports like KPU’s Student Support. Send out regular communications about upcoming activities and due dates. Participate in forum activities, give timely feedback, and offer opportunities for students to provide you with feedback. Respond promptly to student emails and requests for support. Create group activities for students to engage with their peers (forum discussions, chats, synchronous study groups via video conferencing tools). Community building activities increase engagement, decrease feelings of isolation, encourage accountability, and strengthen self-regulation and time management.

- Exercise empathy and flexibility. Remember the human behind the screen, your students and yourself. Online learning is a whole new world, and though it can be exciting and enriching, it can also be overwhelming and lonely, especially during a pandemic. While structure is important, it need not be rigid. So, be flexible; accept human and technical error; embrace and guide students through detours. Give yourself a break; give your students one; it is ok.

References:

Caldwell, J. (2020, August 24). The Faculty Experience During a Pandemic: Survey Results. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://bccampus.ca/2020/08/24/the-faculty-experience-during-a-pandemic-survey-results/

Ejubović, A., & Puška, A. (2019). Impact of self-regulated learning on academic performance and satisfaction of students in the online environment. Knowledge Management & e-Learning, 11(3), 345-363. doi:10.34105/j.kmel.2019.11.018

Kim, H. J., Hong, A. J., & Song, H. (2019). The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1). doi:10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3

Kwantlen Polytechnic University. (2020). Summer 2020 Remote Learning Survey.

Martin, Andrew. (2020). How to Optimize Online Learning in the Age of Coronavirus (COVID-19): A 5 Point Guide for Educators.

Parkes, M., Stein, S., & Reading, C. (2015). Student preparedness for university e-learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 25, 1-10. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.10.002

Gillian Sudlow

Gillian has been supporting learners in their journey to develop their skills and obtain their educational goals for over twenty years. She is a fierce advocate for open access to education and her scholarly interests include competency-based assessment, micro-credentials and open pedagogy. She is excited to work with the inspiring and dedicated team in KPUs Teaching and Learning Commons and is looking forward to supporting faculty with consultations on instructional design and assessment, particularly in blended and online formats.