Cultural Humility

Introducing Cultural Humility

When we set out on the journey of developing intercultural teaching practices, the diversity of frameworks and perspectives available can be overwhelming. Choosing a framework to guide our own complex process of intercultural development can feel confusing. Spitzberg and Changnon (2009) note that among the dozens of frameworks available, there is no one fixed definition of what it means to develop effective ways of being and relating in intercultural environments. Commonly, frameworks for intercultural development focus on the idea of intercultural competence, which may include having the motivation, attitude, knowledge, and skills to relate across similarities and differences.

The idea of intercultural competence, though common, has been challenged. Shi-Xu (2001) argues that common conceptions of intercultural competence fail to consider that our development in this area cannot focus simply on our own skill acquisition. Intercultural interactions always involve our dialogue partners, and always occur in a specific context shaped by historical and situational factors that often involve a power imbalance. When applying this concept to intercultural teaching practices, this means that I cannot measure my effectiveness simply through my own self-assessment, but that consideration of my intercultural teaching practice must take into account how my students experience our intercultural encounter.

Cultural humility, first conceptualized by Tervalon & Murray-García (1998) challenges the idea that intercultural development is an individual competence. Instead, cultural humility defines intercultural growth as a process shaped by regular self-reflection, self-critique and lifelong learning. This process also recognizes the power imbalances inherent in the relationship between professionals and those they serve.

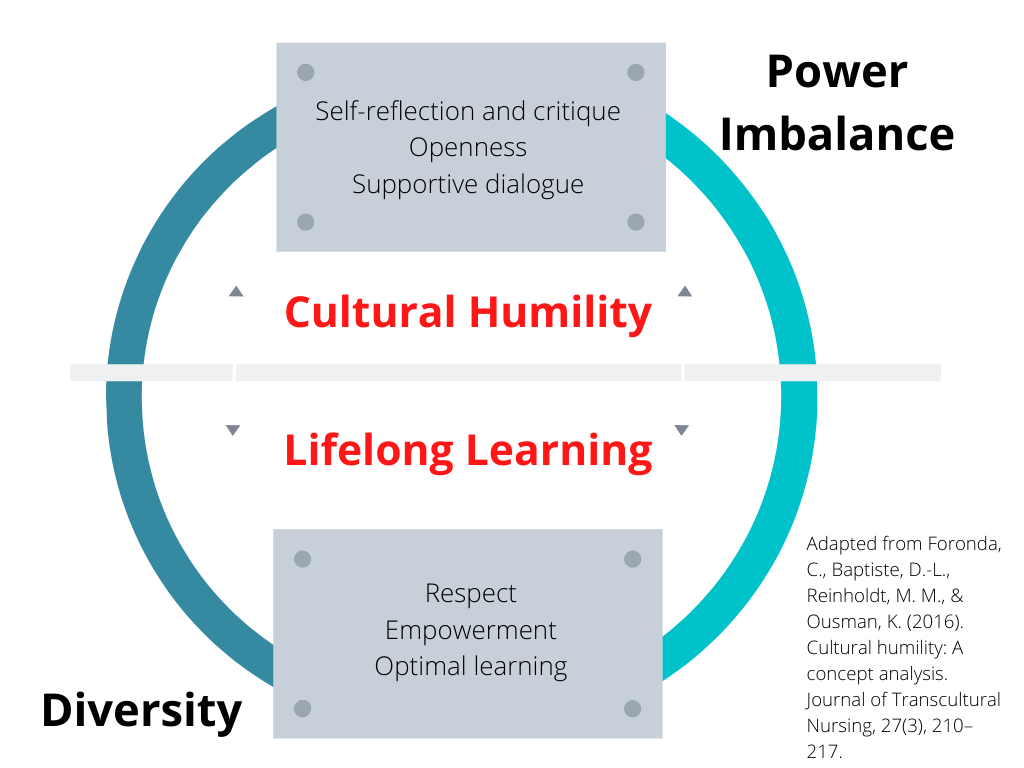

Foronda et al., (2016) analyze the concept of cultural humility, looking at its context, components, and results. Cultural humility acknowledges two contextual realities: the presence of diversity, and the presence of power imbalances, particularly those held in the context of professional practice. Enacting cultural humility incorporates three foundational practices: self-reflection and critique, openness to learning, and supportive dialogue that asks genuine questions and offers our conversation partners (i.e., students) genuine opportunities to share their own experiences and needs. The practice of cultural humility can result in respect, empowerment, and optimal intercultural learning. Cultural humility does not consider intercultural development as a process of learning about “others” and their (assumed) cultural characteristics; such approaches can lead to ways of thinking that result in stereotypes and continue practices that result in exclusion and Othering (Holliday, 2010). Rather, cultural humility seeks to understand our students’ experiences and values as they share them with us in relationships.

How Cultural Humility Guides Intercultural Development for Educators

Cultural humility is most often used as a way to understanding intercultural relationships in health care, social work, and counselling psychology. I believe that this framework, though less commonly used in education, has much to offer us as we consider the development of our own intercultural teaching practice.

First, cultural humility acknowledges that intercultural development is not the acquisition of a body of knowledge, but a way of being in relationship with our students. Often, we may feel uncertain if we don’t have information about our students’ backgrounds or prior life experiences. The cultural humility perspective tells us that our knowledge of our students is best gained in relationship with them. Rather than identifying students according to (assumed) cultural or behavioural categories, we are free to enter into relationships with students without assuming or knowing their needs, while creating space to learn from our students about their own experiences, values, and desires. Beginning this dialogue with students can be as simple as asking students to write a short letter early in the course, or attend a short office hours appointment in the first weeks of the class.

Second, cultural humility acknowledges that intercultural learning is a lifelong practice. Paradoxically, focusing on achieving and demonstrating competence can cause us to move away from intercultural situations that create anxiety for us. Dervin (2016) highlights that a movement away from competence-oriented understandings of interculturality requires us to hold an understanding that we will make mistakes, from which we will continue to learn and seek to change.

Third, cultural humility acknowledges that intercultural practices involve both individual and institutional ways of being (Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998). Even as we consider our own individual cultural humility, we also create space to dialogue with each other about how our broader institutional practices help or hinder genuine interculturality. For example, we might consider with colleagues how normative practices within our discipline might impact students with non-dominant cultural identities.

Lastly, cultural humility acknowledges that interculturality in the context of our professional practice requires that we consider the power differences between ourselves and our students. The cultural humility framework was developed in the context of addressing interculturality within systems of professional relationships, where inequalities exist because of status and role differences. Cultural humility requires us to consider how our position may allow us to assert our cultural norms in ways that diminish our students’ cultural knowledge.

In my own experience and development, learning about the cultural humility framework has shaped my own practice in several important ways. The framework interrupted my tendency to try to understand students primarily in the context of their national cultures and prompted me to consider how I could more accurately understand how students’ cultural identities shape their learning as unique individuals. Understanding my own intercultural development within the cultural humility framework has deepened my understanding of my own journey as ongoing, knowing that critical reflective practice will continue to be a part of my intercultural relating and teaching into the future.

While many approaches to interculturality exist (some arguably superior to others), I believe that cultural humility offers a strong foundation for thinking about intercultural development as educators. A strong framework for intercultural development must acknowledge the need to build intercultural relationships by allowing our students to articulate their stories, identities, desires, and needs. Intercultural development is not a competence that we will achieve “once for all”, but an ongoing journey of growth and development as we continue to pursue inclusive, equitable, and just learning environments for our students.

References

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: A theoretical and methodological toolbox. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D.-L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

Holliday, A. (2010). Cultural descriptions as political cultural acts: An exploration. Language and Intercultural Communication, 10(3), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708470903348572

Shi-Xu. (2001). Critical pedagogy and intercultural communication: Creating discourses of diversity, equality, common goals and rational-moral motivation. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 22(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860120094000

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2–52). Sage Publications.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

Christina supports faculty in their journey of understanding and enriching learning for culturally diverse students, while aiming to facilitate a more joyful intercultural teaching experience. In addition to her work in the Teaching and Learning Commons, her KPU Learning Strategist role allows her to see the learning process from the student side and to integrate her understanding of both faculty and student perspectives. Her educational background includes applied linguistics and educational studies, and her roles have included ESL instructor, literacy consultant, researcher, and adult educator in both Canadian and international contexts. Christina facilitates workshops, connects faculty with relevant resources, and is available for individual consultations.