Where Hummingbirds Take Flight: Restorative Justice & the Post-Secondary Classroom

My name is Alana and I offered to write this blog to share some of my personal experiences and research findings related to the field of restorative justice and post-secondary education that might have resonance with other faculty.

I am KPU alum and completed my first two years at Kwantlen College before transferring to the Criminology program at SFU. Although I have been teaching at KPU for 15 years, I still feel such gratitude for having experience on both sides of the lectern and being part of the KPU community. I was introduced to restorative justice at SFU by Dr. Liz Elliott. When taking her course, I experienced a profound transformation that permanently altered my thoughts, behaviour, relationships, and vocational pursuits. In the years that followed that transformative moment, I became immersed in restorative justice philosophy and practice in prisons, communities, youth justice, and school environments. My doctoral dissertation was directly related to transformative learning and restorative justice, and I have now taught hundreds of students in courses on Restorative Justice. Liz would call students like me, hummingbirds.

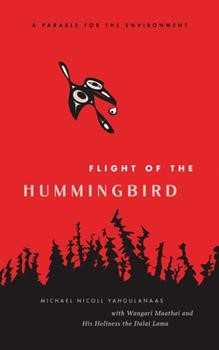

The hummingbird has become a symbol for restorative justice in parts of British Columbia and beyond and is based on the story “The Flight of the Hummingbird” by Haida author Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas. You can watch this short, animated clip of the story here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=naj6zZakgEg

In this story, a great forest fire was raging and all the animals fled and watched from afar as their homes burned. Only Dukdukdiya, the little hummingbird, would not abandon the forest. Flying back and forth between a stream and the fire, she dropped water on the flames, bead by bead. When asked what she was doing, without stopping, Dukdukdiya looked down at all of the animals and said, “I am doing what I can.”

Although a parable for the environment, restorative justice advocates resonated deeply with “The Flight of the Hummingbird.” A Hummingbird lecture series and restorative justice award were created in honour of Liz Elliott following her death in 2011. A totem pole dedicated to Dr. Liz Elliott with the central image of the hummingbird now welcomes all to the Criminology department at SFU.

Like many of you reading this, I didn’t have any special training when I started as a sessional university instructor. Much of what I brought to this role, I borrowed from teachers like Liz who had inspired me. Some of the approaches I reply on include circle process, experiential learning, and storytelling by people with lived experience with the (in)justice system. I try to model vulnerability, humility, sharing, trust and I use restorative justice practices to address issues related to student conflict, lateness/attendance, and academic dishonesty.

On the last day of my restorative justice classes, I always read “The Flight of the Hummingbird” aloud. I have never been able to finish it, without choking up with emotion. One of my students felt so moved by the course and the story, she got a hummingbird tattooed. This student is now a medical doctor. Not to mention a beautiful human.

She says,

The hummingbird to me is strength, courage, compassion, dedication, and zeal. She is a real go-getter; innovative and creative. She is not confined to a 4-walled-box, conforming to what the rest of the world does. When I heard of the story of the hummingbird, I felt empowered. I recognize that I cannot put out fires alone; but like the hummingbird, I don’t want to let this get in the way of my setting an example for how I hope to see the world unfold. I want to build communities, not allow for them to be destroyed by anger, shame, and neglect. I want to heal, not harm. I want to be a hummingbird, and I want to do all that I can.

This quote is one of hundreds in a data set collected for my doctoral research from students who completed the same restorative justice class that had been transformative for me. The research confirmed that while the content of the course was “Restorative Justice,” what made it transformative for me and so many others was the unique andragogy.

Restorative justice seeks meaningful and collaborative ways to address the unique needs of people and relationships affected by harm. Although the roots of this approach can be traced to various ancient, Indigenous ways of knowing and being from around the globe, Western approaches to restorative justice emerged in Canada in the 1970s as an alternative to punishment through the legal system.

Restorative processes are increasingly being considered as a response to harm outside of criminal justice matters in schools, workplaces, and to issues arising within families and communities. Morrison, Thorsborne, and Blood’s (2005) review of the emergence of restorative justice in primary and secondary schools in the early 1990s demonstrate how this approach can facilitate social change through developing healthy relationships across the school community. When introduced in schools as an alternative to punitive, prescriptive policies such as zero tolerance, restorative justice results in fewer suspensions, expulsions, and referrals to law enforcement (González, 2012). There is a group of us at KPU who have been meeting for two years to consider how to bring more restorative approaches to our community to prevent and respond to harm and conflict in our classrooms and beyond.

Restorative justice philosophy is about taking action to promote the overall health and well-being of people. It is both a personal and collective commitment to mutual care, “with a corollary emphasis on relationships and a recognition that healthy individuals do not exist in isolation” (Harris, 2006, p. 120). This conception of restorative justice is grounded in a relational view of the self which “recognizes not only that we live in relationships with others but also that relationship and connection with others is essential to the existence of the self” (Llewellyn & Downie, 2011, p, 4). This commitment to attending to and nurturing relationship is evident with educators, administrators and staff that I have the pleasure of working with at KPU.

Morrison (2007) notes that social institutions play a key role in framing our behavioural choices by formally and informally regulating patterns of interaction and behaviour and (p. 98). Post-secondary classrooms often expose students to ideas and experiences that can shift their perspective and either inspire or erode hope (Morrison, 2007). These individual experiences can collectively lead to more substantial social change. According to Breunig (2005), schools can both prepare people for future work in the world “that is,” while still offering them a vision of what “could be.” What “could be” is the development of a more socially just world (Breunig, 2005, p. 112). University students have the potential to either contribute to the status quo or be part of a change. As Zhang (2013) notes:

…the college setting is a prime opportunity to engage young adults when they may be more receptive to inner transformative experiences. Away from familiar environments of their families, college should be a time where students question, test, and refine the values they have grown up with. (p. 287)

I didn’t have a name for the profound shift in thinking and acting that took place in my restorative justice class until I learned about transformative learning theory during a graduate level education course. Anderson and Anderson (2001) define a transformative learning as learning results in a radical shift from one state of being to another, so significant it requires a shift of culture, behavior, and mindset (p. 39). Transformative learning theory denotes that the purpose of education is towards personal and social transformation through critical reflection, discourse, and action. Transformative learning is considered a form of critical pedagogy in which learning aims to empower students as agents of change, rather than filling them with information to confirm and perpetuate what currently exists in the world. This theory and its associated practices offer innovative, critical approaches to education.

Transformative learning theory rejects traditional forms of instructor-centered, rote teaching in pursuit of collaborative and experiential approaches where both teacher and student have redefined roles. Such approaches are partially inspired by the dissatisfaction with traditional forms of education, motivation that mirrors investment in restorative justice as an alternative to the contemporary justice system.

I saw the connections between restorative justice and transformative learning immediately and found others also made this connection (Adamson, 2012: Toews, 2013). Both approaches shared principles such as emotional engagement, direct participation, and a focus on dialogue, relationality, and critical reflection.

I realized that the restorative justice andragogy that I had been modelled by Dr. Elliott and now was engaged with in my own teaching shared a great deal with transformative learning. Also referred to as restorative justice andragogy, restorative justice education is “inclusive, participatory, reflective, flexible, and respectful” (Gilbert, Schiff, & Cunliffe, 2013, p. 49). This approach centralizes restorative justice practices such as the use of the circle, personal reflection, community building, dialogue, and collaborative decision-making.

My research found that 78% of students who participated in restorative justice education reported a transformative learning experience. Related to this perspective transformation were concrete changes in actions. These finding aligned with past research of a similar nature where students reported personal growth, enhanced communication skills and empathy which led to more meaningful relationships. Students were integrating the restorative principles and processes within their personal and professional lives. One student reported moving the stationary bikes from rows into a circle for the spin classes she taught so she could create more sense of connection and community. Another student who had since graduated and become a police officer said they used restorative justice during almost every shift as they sought non-punitive, collaborative resolutions to the interpersonal conflicts and harms they were called to.

One student stated, “I was deeply impacted. I was forever changed. I had no idea what the course was about and what it meant when I signed up. It was the most amazing and life altering experience. I saw the world entirely different.”

Another said, “[The course] changed how I view my relationships and the weight or the importance that I place on them now. Especially with my mother. I recall before we used to get into a lot of fights but after restorative justice I saw the meaning or importance behind relationships.”

Students who experienced transformative learning also were more likely to engage in volunteer work and pursue vocations within human services. A third of the students in the study said that this course inspired them to take more courses in restorative justice and/or Indigenous studies and to select other courses with non-traditional structures.

In terms of andragogy, students indicated that guest speakers combined with safe spaces in circle to share, be heard, and to hear from others had the most impact on them. One student noted, “Having guest speakers share their stories took the class to another level, the impact their words had on me will be with me forever.” Also of note was the care and relationship between students and with the instructor.

The research findings and my personal experience will likely not be a surprise for many of the faculty reading this. These merely affirm so much of what KPU promotes through our mandate, policies, and teaching and learning initiatives such as the Foundations of Teaching Excellence, emotional intelligence, experiential learning, decolonizing education, and service learning. I feel grateful to be part of an institution that encourages us to provide transformative learning opportunities for our students. In these times of uncertainty, I welcome the opportunity to be fly with other hummingbirds who are just doing what we can.

References

Adamson, C. (2012). Restorative practices: Graduate students’ perspectives seen through a transformative learning lens (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Lesley University, Cambridge, MA

Anderson, D., & Anderson, L. (2001). Beyond change management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Breunig, M. (2005). Turning experiential education and critical pedagogy theory into praxis. Journal of Experiential Education, 28(2), 106-122.

Gilbert, M., Schiff, M., & Cunliffe, R. (2013). Teaching restorative justice: Developing a restorative andragogy for face-to-face, online and hybrid course modalities. Contemporary Justice Review: Issues in Criminal, Social, and Restorative Justice, 16(1), 43-69.

González, T. (2012). Keeping kids in schools: Restorative justice, punitive discipline, and the school to prison pipeline. Journal of Law and Education, 41(2), 281-335.

Harris, K. (2006). Transformative justice: the transformation of restorative justice. In D. Sullivan, & L. Tifft (Eds.), Handbook of Restorative Justice (pp. 555-566). New York, NY: Routledge International.

Llewellyn J. & Downie, J. (2011). Introduction. In J. Llewellyn & J. Downie (Eds.), Being relational: Reflections on relational theory and health, law and policy (pp. 1-12). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Morrison, B. (2007). Restoring safe school communities: a whole school response to bullying, violence and alienation. Cullompton, Annandale, N.S.W.: Federation.

Morrison, B., Blood, P., & Thorsborne, M. (2005). Practicing restorative justice in school communities: the challenge of culture change. Public Organization Review: A Global Journal, 5, 335–357.

Toews, B. (2013). Toward a restorative justice pedagogy: Reflections on teaching restorative justice in correctional facilities. Contemporary Justice Review: Issues in Criminal, Social, and Restorative Justice, 16(1), 6-27.

Zhang, A. (2013). Service learning as civic and spiritual engagement. In J. Lin, E. Oxford, & E. Brantmeier (Eds.), Re-visioning Higher Education: Embodied pathways to wisdom and social transformation (pp. 285-298). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Alana Abramson

Alana has been involved with the field of restorative justice as an academic, trainer, and practitioner since 1999. She has written about the roles of police and community in restorative practice while completing her Masters Degree in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University. Her doctoral work examined student's experiences of transformation through restorative justice education at the post-secondary level. Alana has extensive practical experience implementing restorative approaches in prison, school, and community settings. She brings a strong passion, refined skill and authentic caring to her teaching, practice, volunteer work, and training. Alana is grateful to live within the Secwepemc territory (Kamloops, BC).