A Rose by Any Other Name: Competency & Mastery-Based Learning and Assessments

Introduction

In the ever-changing landscape of Canadian higher education, discussions persist around the “best” pedagogical approaches to student learning, instruction, and assessment. Traditional education often relies on seat time, percentage-based grading, and conventional “pen and paper” assessments like essays and exams (Malan, 2000; Diegelman-Parente, 2011; Sturgis, 2014).

Non-traditional education, particularly evolving over the last century, prioritizes students’ ability to apply learned content. Benjamin Bloom is often considered as a “founding father” of the education system in the past several decades due to his work on mastery-based learning and the development of his taxonomy (Guskey, 2012). This Taxonomy describes the process of learning and developing mastery of a competency as outlined amongst three core domains: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective. Each domain contains measurable action verbs organized thematically and progressively in terms of the complexity or higher-order of that action verb.

This shift aligns with Competency-Based Education (CBE), an age-old concept dating back to Medieval guilds (Compayré, 1897; Denham, 2002; Ogilvie, 2014), which used a competency-based model with performance scales of “apprentice, journeyman, and master.” In fact, this model has remained fairly unchanged as a scale and was developed alongside medical education and training to develop Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) (Desy, Reed, & Wolanskyj, 2017; Tractenberg, Wilkinson, Bull, Pellathy, & Riley, Joan, 2019).

In this blog, we will delve into the core concepts of Competency-Based Education CBE) and Mastery-Based Learning (MBL), exploring their significance and providing examples across various disciplines and subject areas.

Competency-Based Education (CBE): A Paradigm Shift

Competency-Based Education (CBE) represents a transformative approach where learners progress based on their mastery of specific knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes (competencies) rather than adhering to rigid timelines (Sturgis, 2014; Gervais, 2016; Simonds, Behrens, & Holzbauer, 2017). This has resulted in a focus less on students being able to describe what they have learned, but more on students demonstrating how they can apply this new knowledge.

Modern education originated out of the idea that a certain amount of time spent on a concept was required to ensure proficiency. In lower education this was referred to as the “Carnegie Unit” (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1906), and in higher education as the “credit hour” (LeBlanc, 2021). The credit hour has remained as the foundation of the semester system in higher education ever since; however, CBE offers a paradigm shift away from the credit hour to competencies instead as the “common currency” of learning (LeBlanc, 2021, p. 25). This notion is espoused through CBE and MBL as learning is the constant and time can become the variable, rather than the other way around (LeBlanc, 2021).

In CBE, assignments are more focused on assessing demonstrable evidence of student learning rather than assessing the completion of tasks that [hopefully] infer knowledge acquisition and retention. According to William Spady (1994), a key proponent of CBE (developed outcomes-based education, which was referred to as “mastery-based learning” under Bloom in the early 1960s), the approach seeks to create educational systems that ensure students demonstrate competence in the essential content and skills. Simonds et al. (2017) further argue that students’ learning within CBE have “heightened engagement in the learning process” (p. 413) – which makes sense when the learning is about the student rather than the process and product. Moreover, EDUCAUSE (2014) adds that students are “more active, engaged, and motivated when working with coursework that is challenging but within their capacity to master…by linking progress to mastery, avoiding boredom for those moving quickly and frustration for students who need more time” (EDUCAUSE, 2014).

This paradigm shift is designed to accommodate diverse learning styles and ensure that students truly grasp the content before moving forward. For example, Malan (2000) argues that “competency-based education also supports the notion that the learner is accountable for his or her own achievements” (p. 23). This is a departure from assessments being the indicator of achievement as determined by the instructor (a more subjective system), and instead focus on what the learner can do.

While we have certainly come a very long way in education in the last millennia, CBE has evolved, expanded, and branched out particularly in the last century, forming the foundations of many of our current pedagogical frameworks and theories. Drawing from educational theorists and their frameworks such as Ralph Tyler, John Carroll, Benjamin Bloom, and Fred Keller (Gervais, 2016), CBE developed into one of the predominant means of assessing learning.

There are a number of terms that are currently used, and often interchangeably (and inaccurately), to describe very different processes and theories of education, learning, and assessment – but all generally fall within the larger umbrella of Competency-Based Education. For example, there is mastery-based learning, outcomes-based education, standards-based education, objectives-based education, etc. For the purposes of this blog, Mastery-Based Learning (MBL) will be discussed under the umbrella terms of CBE.

Characteristics and Elements of Competency-Based Education and Mastery-Based Learning

As Mastery-Based Learning (MBL) falls under the umbrella term of CBE, there are number of shared characteristics and elements (Malan, 2000; Le, Wolfe, & Steinberg, 2014; Sturgis, 2014; Gervais, 2016; C-BEN, 2017; Simonds et al., 2017):

- Student progression is based on mastery of a concept (competencies)

- Learning outcomes are written to support the competencies they are based on

- Development of what knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes (KSAs) are required to demonstrate mastery; and the acquisition and application of the competencies

- Assessments are authentic and varied, closely aligned with the competencies, with the goal being the engagement in learning rather than creation of a final product

- Time-independent; individualized supports for learners to reach mastery at their own pace

Where MBL starts to depart is more to do with the assessment of assignments. Assignments are generally graded using a mastery-based rubric which delineates the scales between not achieving mastery and achieving mastery. At KPU for example, we use MAS/NCG for this delineation; this allows for integration of a CBE framework within traditional semester time constraints. CBE can absolutely use mastery-based grading, but it is not mandatory as the focus is more on the development of sound, well-structured competencies, than the scale labels.

Implementation of Competency-Based Education

Here are some examples of how specific disciplines might adopt and implement CBE as a framework in their course and/or instructional design.

1. Nursing

As previously mentioned, many medical-based programs, including nursing, use Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME), with competencies encompassing clinical skills, communication, and critical thinking. Many of the competencies are imposed from regulatory or accreditation boards and are based around standards/competencies within the various roles a nurse will undertake. Rather than advancing based on semesters, nursing students progress upon achieving proficiency in each competency, ensuring they are well-prepared for the dynamic healthcare environment (Desy et al., 2017; Tractenberg et al, 2019). Modern nursing programs currently use a “novice” to “expert” scale levels of competency to determine student’s current level of mastery (Benner, 1982)

2. Information Technology

An Information Technology (IT) competency-based framework might delineate programming proficiencies, problem-solving abilities, and ethical considerations. Students in IT programs advance when they demonstrate mastery in web development, algorithms and coding, troubleshooting, and ethical decision-making, fostering a well-rounded skill set aligned with program outcomes and competencies.

3. Graphic Design

A Graphic Design competency-based framework might address specific techniques, colour theory, and principles and elements of design. Graphic Design students advance as they exhibit proficiency in graphic design software, application of elements of design of a webpage, or engaging in the ethics of AI-created artwork.

Mastery-Based Learning (MBL): Focusing on Proficiency

Mastery-Based Learning (MBL) reinforces the idea that students should master the specified KSA before progressing, irrespective of the time it takes. This student-centred approach allows for a deeper understanding of the subject matter and encourages self-paced learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). The concepts are presented in focused units followed by formative assessments to gauge the learner’s degree of mastery towards the learning outcome; this is usually an ongoing process (Guskey, 2002; C-BEN, 2017).

It is also an instructional method and impacts the course and assignment design and materials. Diegelman-Parente (2011) notes, “our ultimate goal as educators should be that students leave our classes mastering the material, regardless of how it is done or how long it takes to do so” (p. 50). As such, students who are unable to master a concept must be provided with constructive feedback and supplemental instructional guidance in or to determine how to meet and achieve mastery at the next assessment point (Diegelman-Parente, 2011). At KPU for example, instructors could design their course to allow completion of self-paced modules within the traditional semester time frame. This would still honour CBE and MBL frameworks as it would allow students to spend more time on content they need to – rather than maintain the pace of the class.

Examples of Mastery-Based Learning in Course and Instructional Design

1. Mathematics

In a mathematics course, students could engage in weekly assessments that gauge their understanding and application of specific concepts (e.g. polynomials, graphing non-linear equations). This routine of formative assessments not only measures understanding, but also provides ongoing opportunities for constructive feedback, timely interventions, and ensuring a strong foundation before moving forward (Higgins, Hartley, & Skelton, 2002).

2. Teacher Education

Practicum Education students participate in in-class discussions to assess their comprehension of pedagogical theories. Students reflect on the discussion and on their contributions through a reflective activity (i.e. developing an ePortfolio, blog, etc.) and further make connections between the discussion and content as related to the competencies for the course and/or program. These discussions and cumulative reflections contribute to a summative evaluation of students’ ongoing comprehension, guiding instructional adjustments and practices based on their understanding (Bell & Cowie, 2001).

3. Computer Science

Computer science students could engage in gamification through online coding challenges with immediate feedback, fostering iterative learning within a summative module. Students could earn digital badges commensurate with their mastery in a given competency. This approach ensures that students not only grasp coding concepts but can apply them effectively, emphasizing cumulative learning and the successful application of knowledge learned (Higgins et al., 2002).

Moving Forward

Transitioning to Competency-Based Education and Mastery-Based Learning necessitates a cultural shift within educational institutions. Research supported practices highlight the implementation of faculty development programs and continuous support for instructors as crucial elements in this transformation (Guskey, 2002; Le, Wolfe, & Steinberg, 2014; C-BEN, 2017; Simonds et al, 2017).

Competency-Based Education and Mastery-Based Learning are student-centred approaches, emphasizing mastery of explicit competencies, and fostering individualized learning journeys. As we witness these transformative models gaining prominence in Higher Education, it becomes evident that the future of education lies in adaptability, competency-based, and personalized learning experiences.

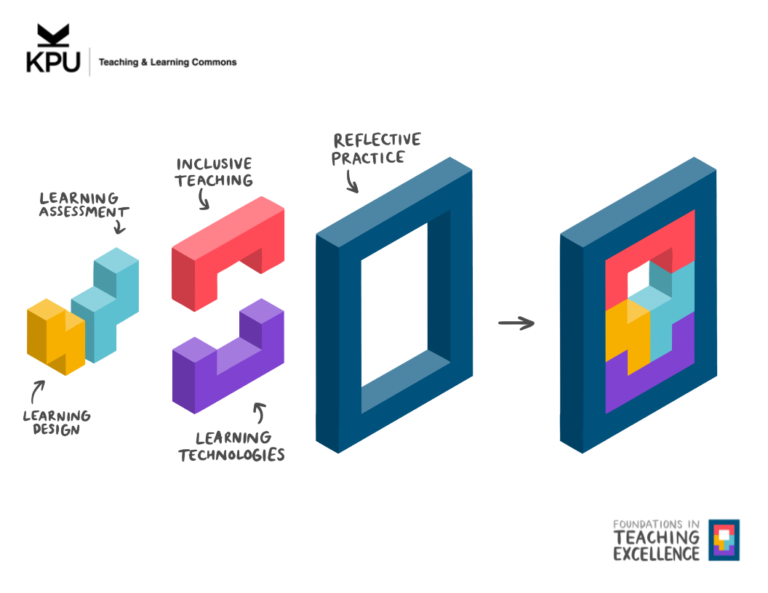

The Teaching & Learning Commons at KPU has dedicated strategists available to assist you with incorporating competency-based education and mastery-based learning into your course and instructional design.

If you are currently using CBE or Mastery-Based Learning in your course, or contemplating incorporating it, stay tuned for our next blog focusing on Mastery-Based Grading (MBG). This blog will help you to design your course from a CBE/MBL perspective.

References

Bell, B., & Cowie, B. (2001). Formative assessment and science education. Dordrecht: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Benner, P. (1982). From novice to expert. American Journal of Nursing, 82(3), 402-407.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (1906, Oct. 15). First Annual Report.

Boston, MA: The Merrymount Press.

C-BEN. (2017, September). Quality framework for competency-based education programs.

Competency-Based Education Network. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from

https://www.cbenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Quality-Framework-for-

Competency-Based-Education-Programs-Updated.pdf.

Compayré, Gabriel. (1897). Abelard and the origin and early history of universities. New York, NY:

Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Denham, Thomas J. (2002). A Brief History of the Major Components of the Medieval Setting –

Emergence of Higher Education in America [Doctoral thesis, Nova Southeastern University].

Desy, J. R., M.D., Reed, Darcy A, M.D., M.P.H., & Wolanskyj, A. P., M.D. (2017). Milestones and

millennials: A perfect pairing – Competency-based medical education and the learning

preferences of generation Y. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(2), 243-250. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.026

Diegelman-Parente, A. (2011). The use of mastery learning with competency-based grading in an

organic chemistry course. Journal of College Science Teaching, 40(5), 50-58.

EDUCAUSE. (2014). 7 things you should know about competency-based education. EDUCAUSE

Publications. Retrieved December 7, 2023, from

https://library.educause.edu/resources/2014/2/7-things-you-should-know-about-

competencybased-education.

Gervais, J. (2016). The operation definition of competency-based education. Competency-based

Education, 1, 98-106. DOI: 10.1002/cbe2.1011.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3),

381-391. DOI: 10.1080/135406002100000512

Guskey, T. R. (Ed.). (2012). Benjamin S. Bloom: Portraits of an educator (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1),

81-112. DOI: 10.3102/003465430298487

Higgins, R., Hartley, P., & Skelton, A. (2002). The Conscientious Consumer: Reconsidering the Role

of Assessment Feedback in Student Learning. Studies in Higher Education, 27, 53-64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070120099368

Le, C., Wolfe, R., & Steinberg, A. (2014). The past and the promise: Today’s competency education

movement. Students at the Center: Competency Education Research Series. Boston, MA.

LeBlanc, P. (2021). Students First: Equity, Access, and Opportunity in Higher Education. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard Education Press, 2021.

Malan, S. (2000). The ‘new paradigm’ of outcomes-based education in perspective. Tydskrif vir

Gesinsekologie en Verbruikerswetenskappe, 28, 22-28. DOI: 10.4314/jfecs.v28i1.52788

Ogilvie, Sheilagh. (2014). The Economics of Guilds. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 169-

192. DOI: 10.1257/jep.28.4.169

Simonds, J., Behrens, E., & Holzbauer, J. (2017). Competency-based education in a traditional

higher education setting: A case study of an introduction to psychology course. International

Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(2), 412-428.

Spady, William G. (1994). Outcome-Based Education: Critical Issues and Answers. Arlington, VA:

American Association of School Administrators.

Sturgis, C. (2014, January). Progress and proficiency: Redesigning grading for competency

education. International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL).

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561319.pdf.

Tractenberg, Rochelle E., Wilkinson, Melody R., Bull, Amy W., Pellathy, Tiffany P., & Riley, Joan B.

(2019). A developmental trajectory supporting the evaluation and achievement of

competencies: Articulating the Mastery Rubric for the nurse practitioner (MR-NP) program

curriculum. PLoS ONE, 14(11): e0224593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224593

Daniel Benzimra

Daniel is a life-long learner who has a wide variety of educational experience primarily in the K-12 sector, but in higher education with andragogy as well. Daniel enjoys collaboratively problem-solving educational challenges from a student-centered approach. In his role as a Teaching and Learning Strategist, Daniel works directly with faculty to help support the learning needs of their students through pedagogically-sound and evidence-based best practices.

Daniel strongly believes in the value of ongoing education and enjoys furthering his own learning and professional development. Daniel is passionate about meeting the needs of learners, special education, and intentional design for learning.