“Aiming for the Moon”: Designing Assignments for Mastery-Based Achievement

A Mastery-Based Grading (MBG) assignment is an educational assessment designed to evaluate a student’s proficiency in specific competencies that are critical to their field of study. MBG assignments challenge students to go beyond rote memory and instead apply their knowledge to practical, real-world scenarios—encouraging them to reach for the moon in every endeavor!

This educational framework ensures that even if students don’t achieve mastery on every task, their learning journey enables them to ‘land among the stars’—with a robust understanding and the ability to apply the material adeptly before progressing. For further background and context on CBE and MBG, please view our blog: A Rose by Any Other Name: Competency & Mastery-Based Learning and Assessments.

Competency-Based Education & Mastery-Based Grading

In essence, MBG offers the framework for assessment, while CBE outlines what is to be assessed—the competencies that students need to demonstrate to advance. In fact, from an employer-standpoint, CBE and mastery of competencies is more frequently becoming the preferred “proof of professionalism” as CBE “confirms mastery of degree-specific competencies using formative, summative and authentic measures resulting in Pass/Fail [MAS/NCG] performance reporting, instead of a grade-for credit scale” (Williams, Moser, Youngblood, & Singer, 2015, p. 52).

It is important to note that often a shift to this thinking can be stressful for students who are familiar with a more traditional approach. As such, it is recommended to explicitly outline MBG with your students and provide coaching to espouse the value of formative and developmental feedback. In other words, show them the value of “aiming for the moon” compared to “just getting the grade” and moving on.

Rationale for Integrating CBE and MBG

MBG, grounded in CBE, is an excellent choice for aligning education with professional realities, accommodating diverse learning styles, and pacing. As supported by Bloom’s student-centred Mastery Learning theory, the premise is that all students can reach mastery, provided they receive the suitable time and support needed (Bloom, 1984). It ensures competencies reflect real-world standards, advancing beyond traditional models; it ensures that students are not assessed based on mere effort or on the breadth of material covered, but rather on their proven ability to apply these competencies in various contexts.

The Composition of Mastery-Based Grading Assessments

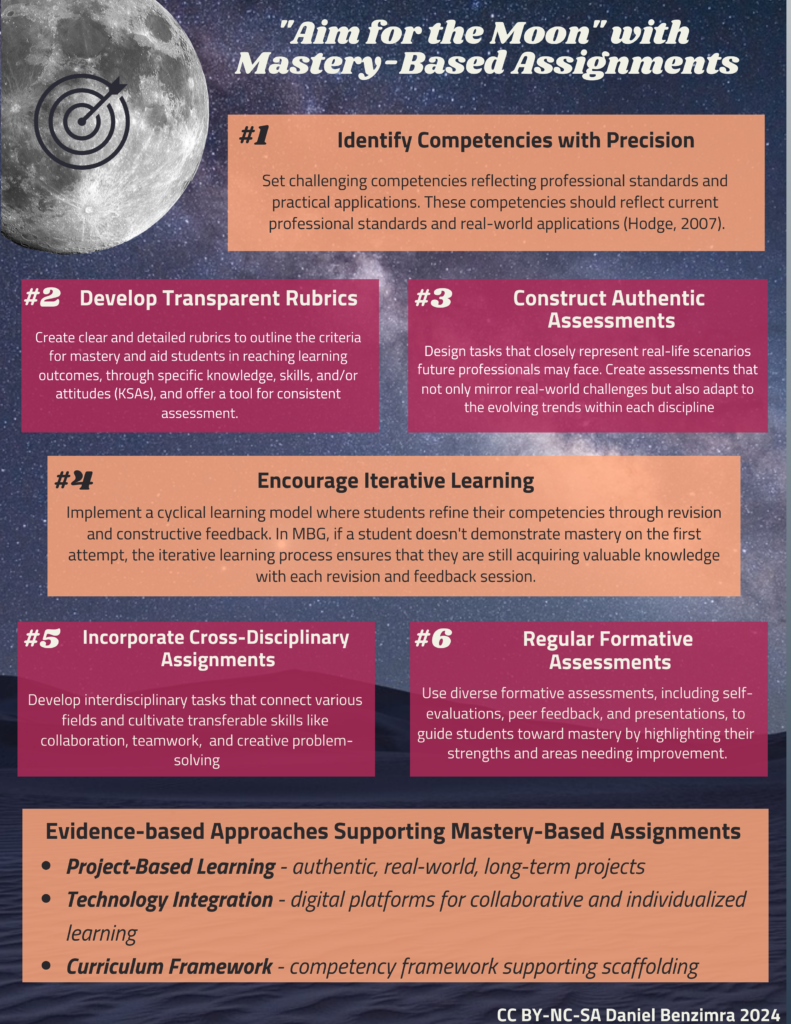

To leverage the full potential of MBG assessments, the following considerations and evidence-based practices are recommended:

Identify Competencies with Precision

“Aim for the moon” resonates with setting competencies that challenge students to reach for the very best in their discipline. Even if students struggle to attain mastery in every single competency, they will still reach a level of understanding and skill—landing among the stars—that sets them apart in their field. These competencies should reflect current professional standards and real-world applications (Hodge, 2007).

Example for Communications Studies:

- Competency – Effectively convey information across various media platforms

- Assessment Instruction: “Demonstrate proficiency in multimedia communication by producing a campaign that engages diverse audiences, integrating text, image, and video components seamlessly”

Incorporating competencies directly tied to professional practices within the assignment instructions underscores the CBE philosophy, thus facilitating MBG

Construct Authentic Assessments

Authentic assessments are assignments that resemble tasks students might encounter in their future careers, which reinforces the integration of learned competencies into real-life scenarios. Create assessments that not only mirror real-world challenges but also adapt to the evolving trends within each discipline.

Example of Literature:

- Competency – Analyze and interpret complex literary works

- Assignment Instruction: “Exhibit mastery by conducting a thematic and stylistic analysis of [specified text], drawing parallels to contemporary issues and demonstrating in-depth literary insight”

Encourage Iterative Learning

MBG promotes a cycle of learning where feedback leads to improvement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Students iterate on their work, progressively enhancing competencies, reflecting continual professional development. The process of “aiming for the moon” implies repeated attempts and learning from each trial. In MBG, if a student doesn’t demonstrate mastery on the first attempt (doesn’t reach the moon), the iterative learning process ensures that they are still acquiring valuable knowledge (landing among the stars) with each revision and feedback session.

Example of Engineering:

- Competency – Application of theoretical engineering concepts to practical design problems

- Iterative Process: “After presenting your initial design prototype, integrate the feedback to enhance its functionality and sustainability, showcasing your adaptive and reflective engineering skills”

Incorporate Cross-Disciplinary Assignments

MBG assessments can benefit substantially from including cross-disciplinary elements, allowing students to connect concepts from different fields and develop a multifaceted view of their studies (Boix Mansilla & Duraisingh, 2007). Design interdisciplinary assignments that encourage the cultivation of essential soft skills like teamwork, ethical decision-making, and creative problem-solving.

Example for Business and Psychology:

- Competency – Conduct integrative market research

- Assignment Prompt: “In collaboration with students from the Psychology department, develop a market analysis that marries psychological insights with business market trends, offering a holistic view of consumer behaviour”

Regular Formative Assessments

Expand the use of formative assessments beyond typical written or online formats by integrating self-evaluation, peer feedback, and oral presentations, thus accommodating multiple learning preferences (Black & Wiliam, 2009). Those who do not meet the highest standard in formative assessments will still benefit from the feedback, improving their understanding and skills (landing among the stars) in a manner that summative assessments alone might not provide. These assessments are essential in MBG as they pinpoint students’ areas of strength and improvement on the path to mastery.

Examples for Mathematics:

- Competency – Solve complex mathematical problems using advanced theories

- Formative Task: “Complete a series of weekly applied math challenges that will be peer-reviewed, to solidify your comprehension and problem-solving ability, leading to mastery”

Develop Transparent Rubrics

Though we will discuss MBG Rubrics in more detail in our subsequent blog, it is worth mentioning rubrics as you are designing your assignments. Rubrics play a critical role in MBG by providing transparent and detailed criteria that describe what mastery looks like (Reddy & Andrade, 2010). They guide students toward achieving learning outcomes, through specific knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes (KSAs), and offer a tool for consistent assessment.

Example for Health Sciences:

- Competency – Apply health promotion strategies at the community level

- Rubric Indicator: “Mastery is evidenced by the ability to devise an impactful public health campaign, tailored to community needs, and grounded in current health science research”

Evidence-Based Practices

Adopting a mastery-based approach entails the incorporation of diverse evidence-based practices to support the student’s journey towards mastery of the concepts and competencies. By evidence-based practices, such as those listed below, within the MBG framework, educators ensure a rich, dynamic learning process that truly caters to students’ mastery and preparedness for their future careers.

- Project-Based Learning

Engage students in long-term projects where they can apply course concepts over time. Structure long-term projects with clear objectives, milestones, and regular performance checkpoints to maintain student engagement and accountability throughout the learning process.

- Example for Environmental Studies: Assign a semester-long project where students must address a real-world environmental challenge, requiring continuous application of their environmental science knowledge to develop a solution

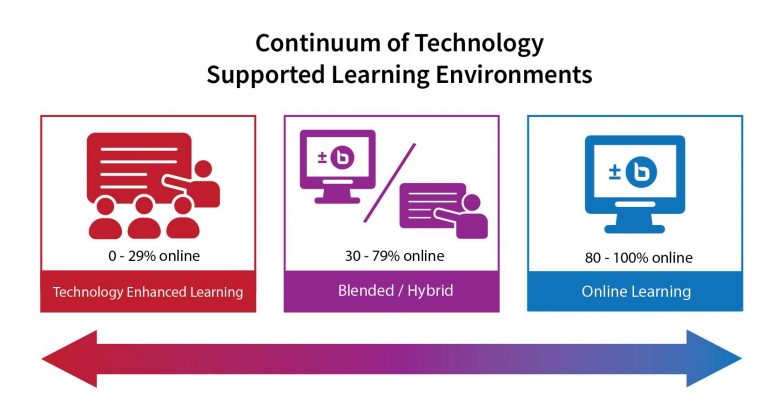

2. Technology Integration

Employ adaptive platforms and digital tools for an individualized and collaborative learning experience. Encourage the use of contemporary collaborative tools that mimic digital workplaces, promoting skill development in digital literacy and teamwork.

- Example for Computer Science: Implement coding platforms that offer immediate feedback and allow students to adjust their code in real-time, fostering a deeper comprehension of programming constructs

3. Curriculum Frameworks

A well-structured competency framework can scaffold the curriculum and guide students to achieve set proficiency levels. Regularly reassess and update curriculum frameworks to incorporate the latest educational research findings as well as changes in professional practices.

Example for Nursing: Use a competency framework that includes patient care, ethical considerations, and technical nursing skills to structure the nurse training curriculum

Conclusion

As educators, we aim for the moon in our academic pursuits, setting high competencies that stretch students’ potential. This moonshot endeavor ensures that even when students face challenges along the way, their efforts allow them to land among the stars, as they accumulate a wealth of skills transferable to future workplaces. This shift towards a competency-focused approach, supported by evidence-based practices, crafts a new academic trajectory abundantly clear in its mission: to honor and support each student’s journey towards mastery. Educators foster an environment where aiming high is the norm, and every incremental step forward is a cause for celebration—a nod to lifelong learning and the continuity of personal and professional growth.

Stay tuned for our next blog in the series, “Pass with Flying Colours”: Designing Mastery-Based Grading Rubrics – which will focus on designing rubrics for your MBG assignments.

References

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21, 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2-sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013006004

Boix Mansilla, V., & Duraisingh, E. D. (2007). Targeted Assessment of Students’ Interdisciplinary Work: An Empirically Grounded Framework Proposed. Journal of Higher Education, 78(2), 215-237. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2007.0008

Darling-Hammond, L., & Ifill-Lynch, O. (2006). If they’d only do their work! Using a competency-based system to address student motivation to produce quality work. Stanford University, School of Education. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/if-they’d-only-do-their-work-using-competency-based-system-address-student-motivation-produce-quality-work.pdf

Guskey, T. R. (2010). Lessons of mastery learning. Educational Leadership, 68(2), 52-57. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/oct10/vol68/num02/Lessons_of_Mastery_Learning.aspx

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hodge, S. (2007). The origins of competency-based training. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 47(2), 179-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-017-0093

Reddy, Y. M., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930902862859

Reeves, T. C., & Oh, E. (2017). The goals and methods of educational technology research over a quarter century (1989-2014). Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(2), 325-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9485-2

Sturgis, C., & Patrick, S. (2010). When success is the only option: Designing competency-based pathways for next generation learning. Competency Works, iNACOL. Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Daniel Benzimra

Daniel is a life-long learner who has a wide variety of educational experience primarily in the K-12 sector, but in higher education with andragogy as well. Daniel enjoys collaboratively problem-solving educational challenges from a student-centered approach. In his role as a Teaching and Learning Strategist, Daniel works directly with faculty to help support the learning needs of their students through pedagogically-sound and evidence-based best practices.

Daniel strongly believes in the value of ongoing education and enjoys furthering his own learning and professional development. Daniel is passionate about meeting the needs of learners, special education, and intentional design for learning.