Recognize the Whole Person: A Student-Centered Intercultural Teaching Framework

If we asked our students to tell us what is most important in an intercultural teaching practice, what would they say? That’s the question that came to my mind as I began my doctoral research several years ago. I’d read a number of helpful frameworks that provide guidance for my professional development as an instructor (e.g., Dimitrov & Haque, 2016; Killick, 2018; Lee et al., 2017). I’d found them all helpful, but at the same time complex. My reading provided fuel for reflection, but less help for simple, day to day actions. Like many of my colleagues, sometimes the demands of supporting my international students in their academic growth felt like too much, and I wondered how to prioritize.

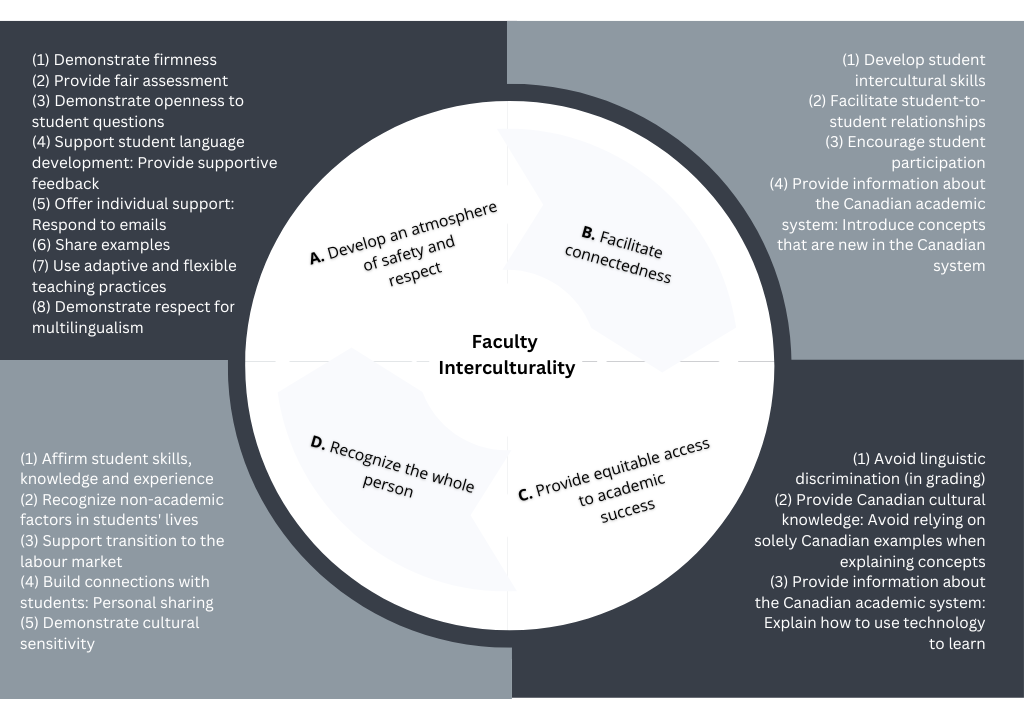

I wondered what a framework of good faculty intercultural teaching practice would look like if we asked our students. After all, they’re the ones impacted by our teaching and the ways we support their learning journeys. I started my research by interviewing 12 participants (either international students, or students who were domestic but beginning their first Canadian education experience). After analyzing the interview data, three participants worked with me to develop a student survey, which 193 additional participants completed. After working through the statistical analysis (with much thanks to KPU colleague Dr. Chris Giles), four main domains of intercultural teaching practice emerged. They are: (1) Develop an atmosphere of safety and respect; (2) Facilitate connectedness; (3) Provide equitable access to academic success; and (4) Recognize the whole person. The diagram below provides a snapshot of the four domains, and the practices that are associated with each.

Develop an atmosphere of safety and respect:

This domain includes practices that provide a respectful, psychologically safe learning environment where students sense they can succeed. It includes actions like demonstrating openness to student questions, responding to emails, and providing supportive feedback along the way. Interestingly, this domain also includes firm and consistent practices, where students do not believe that their peers are “getting away” with poor behaviour.

Facilitate connectedness

Facilitating connectedness is about attending to the relational aspects of learning. Participants shared that they want to build relationships with their peers, and desire that instructors structure classroom activities in ways that facilitate this. Participants also indicated that they want instructors to support them as they develop the intercultural skills that allows them to build relationships in diverse classrooms. Connectedness also includes feeling linked to understanding the Canadian academic system more broadly, so that new and unfamiliar concepts can be mastered.

Provide equitable access to academic success

This domain acknowledges that students arrive in the classroom with different types of valuable knowledge and will require different supports to reach an equal playing field for academic success. For example, students often report that they find learning with technology to be new and unfamiliar. Language is another domain where equitable chances of success were important, as participants reported linguistic discrimination in grading to be a barrier to succeeding. It’s important to note that in other areas of the study, participants shared that they valued constructive feedback on their writing and language use; discrimination was perceived when grade deductions for language seemed overly harsh, or when support didn’t seem readily available.

Recognize the whole person

While a lot of items in the first three domains overlap with many other authors’ work on intercultural teaching, the recognize the whole person domain stood out as being new and different. This is the information that student participants offered that often is outside of our awareness as educators, as we can be more focused on what goes on inside the classroom or online learning environment. Participants shared the challenge of managing large cultural and academic transitions, while at the same time balancing significant paid work commitments alongside study. Other participants shared that they wanted to be viewed as knowledgeable adults, and not just within the role of “international student”.

Whether through recent media attention or personal experience, we’re often aware of the workloads and challenges our students are carrying. Sometimes we forget to acknowledge this out loud. I had a surprising informal conversation with a student last year, who mentioned that instructors often didn’t seem to know about or recognize their students’ complex situations. I was curious about this, knowing from my interactions with faculty colleagues that many colleagues recognize students’ challenges and care deeply. Whole person recognition may involve naming challenges out loud and providing strategies for managing complexities. In addition, it can include recognizing our students’ past life experiences, and how their study fits into larger career journeys and aspirations.

How to Use the Student-Centered Taxonomy: Practical Suggestions

One of the advantages of framing intercultural teaching within a student perspective is that it can help us more easily identify simple actions that we could implement, even if we don’t feel that we have the time or space to become experts in intercultural teaching. For example, items like facilitate student to student relationships (Facilitate connectedness domain) can involve small steps like making space for student introductions, using simple icebreakers, and having students do small group learning activities in class.

One approach might be to choose a single domain – or even a single item within a domain – to experiment with for a few weeks or a semester. In other words, what’s one small, easy change (that students have already identified as impactful) that you’re willing to try.

A second advantage of listening to student perspectives is it can help us resolve some of our own dilemmas. For example, I have struggled to know how flexible to be with student assignment submissions while maintaining my own workflow. Integrating first-person perspectives from a number of students in my research pointed to a perspective that students want some flexibility, but also structure to keep them on track. This personally led me to a balance of allowing one “free” late submission to students per semester, which provides students flexibility for “crunch periods” while encouraging them to stay on track with course work.

We are often inspired and motivated to create compassionate and motivating learning experiences for students. At the same time, we recognize our own capacity and limitations. Listening to the perspectives of students within the student-centered taxonomy, for me, has created a guiding structure for prioritizing practices within my teaching. After all, sustainable intercultural teaching practice is for our students, but also for our own well-being as educators as we too walk within the ecosystem of the global and local factors that impact our classrooms (Ilieva et al., 2014).

In addition to learning from the student-centered taxonomy, my final encouragement is to engage students regularly to find out their perspectives. What’s most important to them? As I found with my research participants, many are delighted with the positive relationships they have with many of their instructors. Our students might just have one or two additional suggestions to make their experience, and ours, even better.

References

Dimitrov, N., & Haque, A. (2016). Intercultural teaching competence: A multi-disciplinary model for instructor reflection. Intercultural Education, 27(5), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2016.1240502

Ilieva, R., Beck, K., & Waterstone, B. (2014). Towards sustainable internationalisation of higher education. Higher Education, 68(6), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9749-6

Killick, D. (2018). Developing intercultural practice: Academic development in a multicultural and globalizing world. http://www.myilibrary.com?id=1032840

Lee, A., Felten, P., Poch, R. K., Solheim, C., & O’Brien, M. K. (2017). Teaching interculturally: A framework for integrating disciplinary knowledge and intercultural development. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Christina supports faculty in their journey of understanding and enriching learning for culturally diverse students, while aiming to facilitate a more joyful intercultural teaching experience. In addition to her work in the Teaching and Learning Commons, her KPU Learning Strategist role allows her to see the learning process from the student side and to integrate her understanding of both faculty and student perspectives. Her educational background includes applied linguistics and educational studies, and her roles have included ESL instructor, literacy consultant, researcher, and adult educator in both Canadian and international contexts. Christina facilitates workshops, connects faculty with relevant resources, and is available for individual consultations.