The Spectrum of Success: Strategies for Designing Mastery-Based Rubrics

In our three-part series on competency-based learning and assessments, the first blog, “A Rose by Any Other Name: Competency & Mastery-Based Learning and Assessments,” grounded in Benjamin Bloom’s Mastery Learning theory, affirmed that all students can achieve mastery with appropriate support and time, highlighting the shift from traditional educational models to Mastery-Based Grading (MBG) and its effectiveness (Nilson, 2015). The second blog, “Aiming for the Moon: Designing Assignments for Mastery-Based Achievement,” discussed how MBG focuses on student proficiency in competencies rather than traditional letter grades, promoting equity, comprehension, and accommodating diverse learning styles (Brookhart et al., 2016; Townsley & Schmid, 2020).

In this final blog in the series, you will learn how to apply the theory and foundational content from the previous two blogs into Mastery-Based Grading rubrics – a specific design choice leaning into evaluating student demonstration of learning along the benefits and pedagogy of Mastery-Based Learning.

MAS/NCG Grading System

MAS/NCG is similar in a way to Pass/Fail, but it actually isn’t binary – generally the MAS has two performance indicators (such as a “basic proficiency” and an “extending”) and NCG has one performance indicator (such as “developing”).

The crucial difference here is that MAS, as mastery, implies a gradation compared to Pass/Fail, which is binary. As such, students can still pass a course but can also pass with “flying colours” (both of which would be MAS), but only “developing” would be considered NCG.

MBG is a method of assessing students using a mastery-based scale to indicate whether the learner has sufficiently demonstrated their learning, as laid out in the learning objectives, to the point they can be considered “mastering” it (Brookhart et al., 2016). Generally, this means that learners have successfully and thoroughly met the learning objective, and that additional review or assessments on that topic would not further their knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes (KSA) for that objective.

Understanding Mastery-Based Grading

Under Policy AC4, Student Evaluation and Grading, KPU has two “competency-based grading systems” – MAS/NCG and EXP/NCG.

KPU has created definitions within this system on the Grades website:

- Mastery Grading System – “a competency-based grading system given to courses that demand a clearly defined high standard of performance, in which the student must demonstrate mastery of all knowledge and/or performance requirements”

- MAS – “Mastery. Student has met and mastered a clearly defined body of skills and performances to the required standard”

- NCG – “No Credit Granted. Student has not met the required standard for the course and/or has not participated to the required level in course activities”

Distinguishing Characteristics between Traditional Grading Rubrics and MBG Rubrics

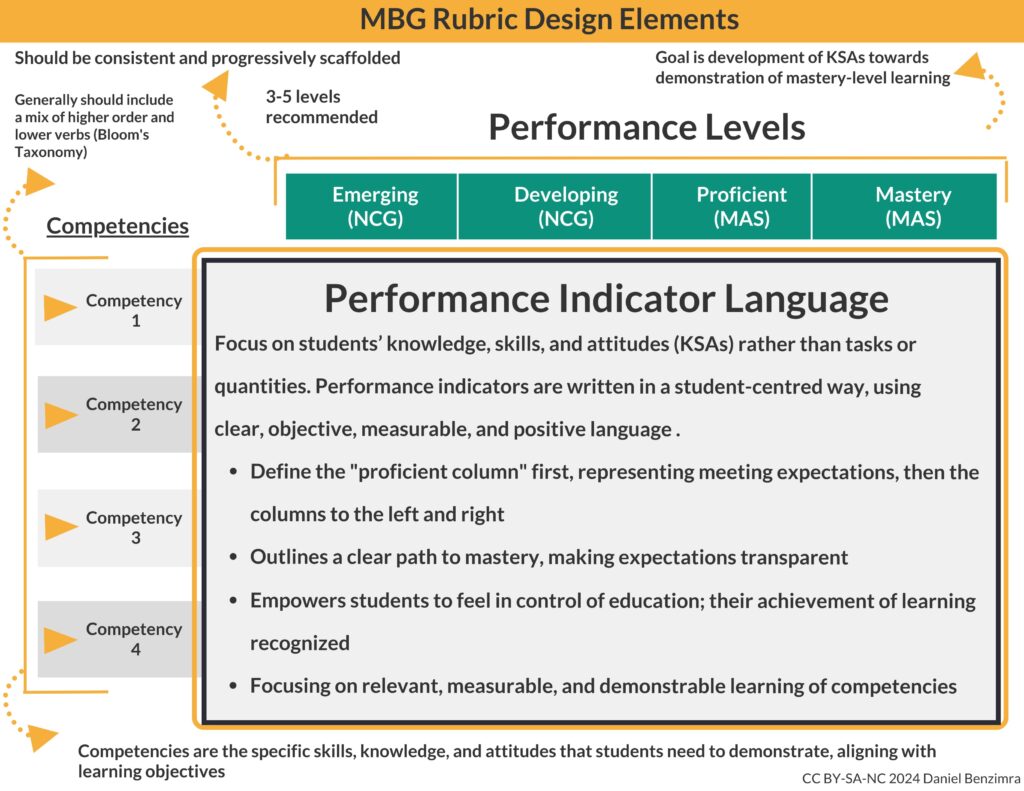

Here are several distinguishing characteristics between traditional grading rubrics compared to Mastery-Based Grading rubrics. The below sections and graphics help to highlight the differences in the focus and intention of the rubrics, the design and inclusion of competencies, as well as the function of the rubric in evaluating student demonstration of learning.

- Refining Assessment: The Distinctive Nature of Mastery-Based Grading Rubrics

Assessment in higher education is pivoting towards frameworks that more accurately reflect student learning and competencies. MBG rubrics present unique features that set them apart from traditional rubrics. These rubrics are not only evaluative but also instructional, shaping learning trajectories towards mastery—central to CBE.

- Formative Function

In mastery learning, rubrics are often part of an iterative process, meant to guide improvement until mastery is reached (Black & Wiliam, 1998). This formative aspect starkly contrasts with the finality of traditional rubrics, which tend to signal the conclusion of an assessment period without an embedded mechanism for improvement based on feedback.

- Growth Mindset Promotion

MBG encourages students to develop a mindset that views competencies as improvable rather than innate (Dweck, 2006). Traditional grading systems may inadvertently foster a fixed mindset by suggesting that abilities are static, which can hinder motivation and engagement in learning. Through supporting students in developing a positive and empowering learning experiences and growth, students are better positioned to want to not just pass, but pass “with flying colours.”

- Amplifying Rubric Effectiveness Through Student Engagement

Supporting students to be part of the rubric creation process can vastly enhance its relevance and impact. By inviting feedback and allowing students to negotiate the criteria and language of performance indicators, educators can ensure the rubric resonates with the learner’s experience, fostering collaboration, encouraging deeper engagement, and ownership of their learning trajectory (Johnson, Becker, Estrada, & Freeman, 2014).

- Integrated Descriptors of Quality

MBG rubrics employ qualitative descriptors that explicitly convey what success looks like at each performance level (Jonsson, 2014). Though this is also generally true of traditional rubrics, it is the intentionality of the design of the rubric, as progressive in the descriptive language, for how the learning can be demonstrated that is important. This nuanced approach aids in setting clear expectations, as opposed to the less detailed traditional rubrics which may not offer the same level of guidance. The design of MBG rubrics accounts for the developmental nature of learning, acknowledging individual differences and allowing for personalized pace (Bloom, 1984).

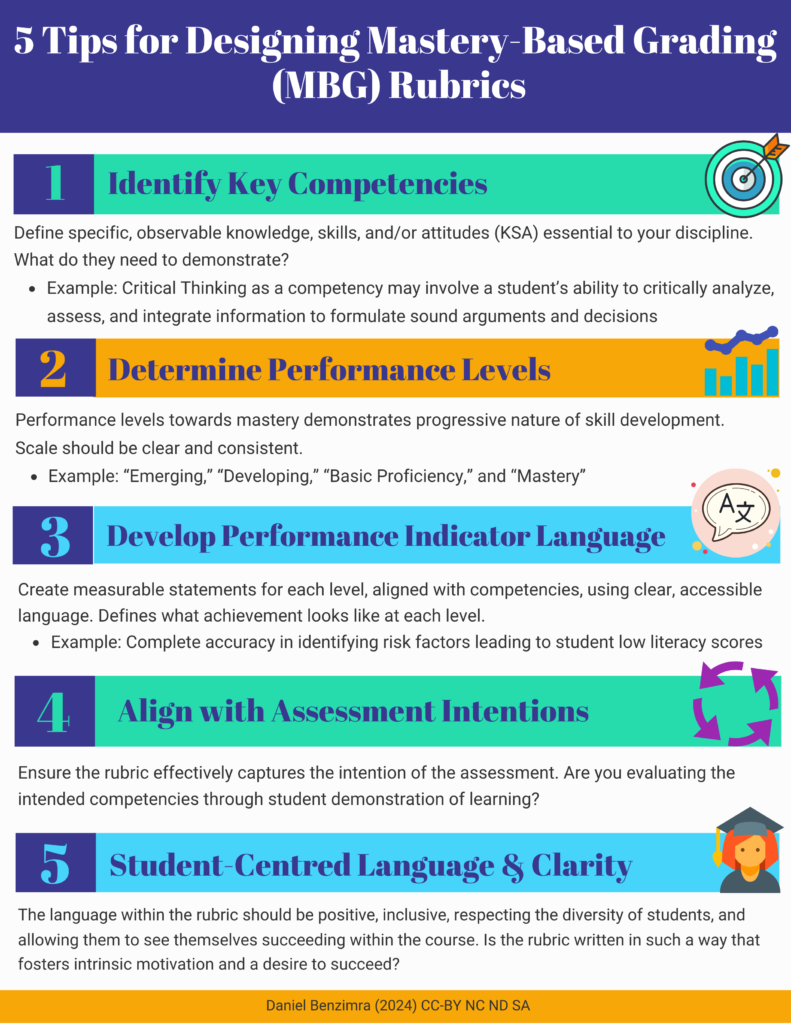

The above infographic provides specific tips for designing Mastery-Based Grading (MBG) Rubrics, with key information highlighted within each tip, to help guide your initial design and set up. The Teaching & Learning Commons further offers support in this area, and we warmly invite instructors to connect with us if you are interested in learning more and/or pursuing this evaluative pathway.

Creating Mastery Based Rubrics in the Moodle Gradebook

Moodle Gradebook is not traditionally set up to facilitate Mastery-Based Grading (MBG) rubrics. To assist instructors, here is a step-by-step Freshdesk article Setting Up Your Moodle Course for Mastery Grading (MAS/NCG) with instructions for creating MAS/NCG rubric in Moodle Gradebook. These instructions also include a video option to demonstrate the steps.

Mastery-Based Grading (MBG) rubrics, distinct from traditional rubrics, embody the principles of Competency-Based Education (CBE), marking a shift towards continuous learning, student empowerment, and mastery of competencies. Traditional grading systems, rooted in colonial frameworks, often marginalize diverse learners and stifle growth. In contrast, MBG rubrics celebrate learning by reframing goals from “pass/fail” to “pass/pass with flying colours.”

These rubrics, defined in actionable terms, highlight progressive skill development and use inclusive language to redefine success. They are pedagogical bridges guiding students towards becoming competent professionals. The future of assessment lies in these transformative tools, which not only gauge but also contribute to student learning. By fostering self-assessment and mastery, and collaborating with students on clear, constructive rubrics, educators can cultivate a culture that celebrates understanding and personalized learning journeys. This approach is poised to redefine success in higher education.

Adopt CBE and MBG rubrics to help create an environment that values every student’s unique path to academic mastery.

Support for Mastery Grading and Setting up Rubrics in Your Course

The Teaching & Learning Commons offers instructors support in building MAS into their courses, including teaching and learning activity considerations, assessment design, and working with competencies. Please reach out at tlcommons@kpu.ca to meet with a Strategist.

References:

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2-sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4-16. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X01300004

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). ‘Assessment and classroom learning,’ Assessment in education: Principles, policy & practice. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Brookhart, S. M., Guskey, T. R., Bowers, A. J., McMillan, J. H., Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., Stevens, M. T., & Welsh, M. E. (2016). A century of grading research: Meaning and value in the most common educational measure. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 803-848. http://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316672069

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Johnson, L., Becker, S., Estrada, V. & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher education edition. The New Media Consortium. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/130341/.

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(7), 840-852. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.875117

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. How People Learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24783.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Spady, W. G. (1994). Outcome-based education: Critical issues and answers. American Association of School Administrators.