by Iuliia Astashova

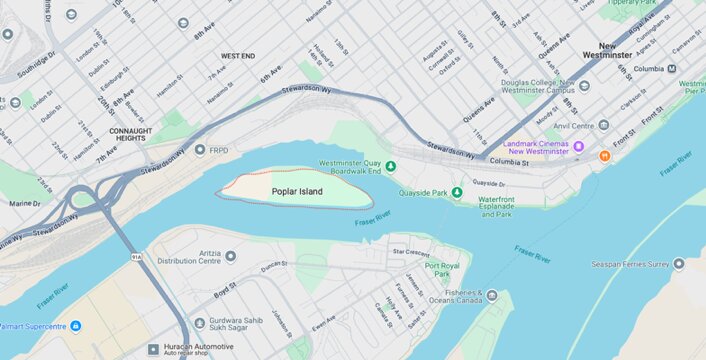

It’s surprising how a part of history or someone’s life can so easily be forgotten, erased, either intentionally or not, leaving behind only distant memories that are now hardly mentioned. These were my first thoughts when I learned about the existence of Poplar Island – a large island that lies in the North Arm of the Sto:lo (Fraser river) between New Westminster and Lulu Island, which was once home to the Qayqayt First Nation.

You can even see it from the New Westminster Quay, where I often walk, but like many others, I knew nothing about it until recently. Curious, I went to look at it specifically, and sure enough – a big, uninhabited island was right there, directly across from residential houses, seeming so lonely and untouched. But this land hides a rich and, at times, painful history that deserves to be known: long before industrialization, it was the land of the Qayqayt First Nation, a Coast Salish community that lived along the Sto:lo – the river that was, and still is, a vital part of their cultural identity.

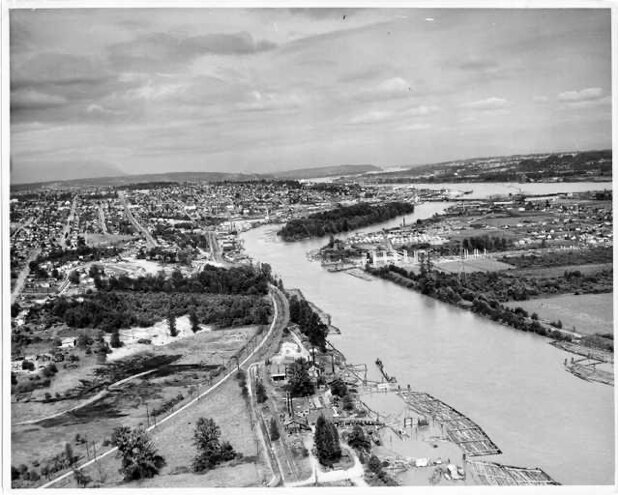

Today, Poplar Island seems abandoned, but in the 20th century, particularly during World War I, it was used for various industrial activities, including shipbuilding, sawmills, and pulp and paper production. Back then, the landscape looked entirely different – the forest that now blankets the island was completely cleared, and there was even a bridge connecting it to New Westminster.

The darkest chapter in Poplar Island’s history unfolded in 1889, during a devastating smallpox epidemic. In a decision made by the mayor of New Westminster, the island was designated a quarantine zone for smallpox victims. However, only Indigenous people were forcibly sent to the island, while European settlers were allowed to isolate in their homes. This divide reflects the racist and discriminatory practices of the time, where Indigenous lives were devalued and denied proper healthcare.

The isolation and neglect resulted in countless deaths, with the epidemic dramatically reducing the population of the Qayqayt First Nation. The island became a mass burial ground for these victims, though little remains to memorialize this tragic history today.

Currently, Poplar Island remains mostly untouched, owned by the government of British Columbia and designated as a natural reserve. Despite its current quiet state, the question of rightful ownership lingers. The land was taken from the Qayqayt First Nation during colonization, and the issue of returning it to them has yet to be resolved.

Today, the Qayqayt First Nation consists of nearly 100 members, with Rhonda Larrabee serving as the Chief. After discovering her Indigenous roots, Rhonda became the first documented member of the band since 1951. She has since been actively working to preserve Qayqayt heritage, promote cultural awareness, especially among children and youth, and file claims to regain land. The Qayqayt is notably “the only First Nation community in B.C. without a current land base” (Axiom News, 2021).

The history of Qayqayt First Nation was unknown for many years and is a sad story. We have worked tirelessly for many decades to ensure the legacy of our ancestors will live on for many generations

Chief rhonda larrabee

The lack of recognition, both in historical records and physical markers, highlights the ongoing erasure of Indigenous presence and stories. It’s crucial to shed light on this island’s past, not only to honor those who suffered but to foster the decolonization of our understanding of history.

References:

Axiom News. (2021, June 17). Reclaiming roots: Unearthing the lost history of Qayqayt First Nation. Axiom News. https://axiomnews.com/reclaiming-roots-unearthing-lost-history-qayqayt-first-nation

CBC News. (2015, December 27). New Westminster looks to future of Poplar Island. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/new-westminster-poplar-island-1.3385018

Douglas College. (2021, June 11). Chief Rhonda Larrabee of the Qayqayt First Nation named Douglas College’s 2021 honorary fellow. Douglas College. https://www.douglascollege.ca/news-events/2021/jun/chief-rhonda-larrabee-qayqayt-first-nation-named-douglas-colleges-2021

Smith, C. (2005, October 27). How Poplar Island fell off the map. The Georgia Straight. https://www.straight.com/article/how-poplar-island-fell-off-the-map

Vancouver Traces. (n.d.). Poplar Island. Vancouver Traces. https://vancouvertraces.weebly.com/poplar-island.html

Leave a Reply