Developing Learning Outcomes

In any educational activity, there are a myriad of discrete and interrelated knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired, reflected on, and put into practice by students. How is an instructor to determine what needs to be formalized in an intended Learning Outcome in the face of so many options and modes of demonstration?

Spady (1994, as cited in Killen, 2000), who created OBE, states that Learning Outcomes are the learning results from students that lead to culminating demonstrations, that is these results and their demonstrations occur at the end of a significant learning experience. An outcome is not a collection or average of learning experiences, but a manifestation of what the learner can do once they have had and completed all of those experiences. This means that outcomes are not simply the things that students believe, feel, remember, know, or understand, rather Learning Outcomes are what students actually can do with what they know and understand.

Considering this and the material that has been covered regarding constructive alignment and backward design, this resource makes the following recommendations around the development of Learning Outcomes:

- Select the most significant and durable learning you want your students to retain after the educational experience for your intended Learning Outcome.

- Select the highest level of learning to describe in your Learning Outcome.

- Choose demonstrated learning that acts as a foundation for subsequent learning.

- Describe learning rather than instructional activity.

- Outcomes are directly linked to assessments; if it can’t be assessed it isn’t an outcome.

- Have all critical components been captured?

Are there knowledge, skills, or habits of mind that will be essential in the future that aren’t currently addressed?

With this guidance in mind, this resource will now move on to exploring the

Structures of Learning Outcomes

All Learning Outcomes use a similar structure. This structure is comprised of the following components:

A Sentence Stem

A Measurable Verb

Knowledge, Skill, or Attitude (KSA)

How the KSA will be Demonstrated

Types & Alignment of Learning Outcomes

A. Types of learning Outcomes

Earlier in this resource, three types of Learning Outcomes were discussed. They were: Program Learning, Course Learning, and Lesson Learning Outcomes. This section will provide details of each of these Learning Outcomes.

program learning outcomes

Program Learning Outcomes (PLOs) are Learning Outcomes from educational activities that occur at the program level. As discussed earlier, Learning Outcomes describe a student’s ability at the culmination of an educational activity, therefore all Program-Level Learning Outcomes will speak to a student’s expected ability upon completion of the program. As a result, PLOs tend to be High-Level Learning Outcomes. This means they will likely use verbs from the top two or three categories of Bloom’s taxonomy, discussed earlier. These Learning Outcomes articulate the overall ability available to graduates of the program. This means PLOs will not reference specific learning tasks or Course Learning Outcomes, but rather will speak to the graduate’s ability to synthesize and apply information available from multiple courses offered throughout the program to specific real-world situations.

Learning Outcomes at the program level will be created before Learning Outcomes of the course or lesson level. This does not always happen in the real world, and ideally, the Program Learning Outcomes will guide the development of Course Learning Outcomes which will guide the development of lessening the outcomes. Generally speaking, Program Learning Outcomes are developed from graduate competencies identified by a team of subject matter experts. These graduate competencies often function as KSAs for learning outcomes moving from general at the program level to specific at the lesson level. As stated earlier, Learning Outcomes at the program level may be motivated, selected by the subject matter experts, or imposed, required by the program, department, institution, or regulatory body (Chan, Fong, Luk, and Ho, 2017).

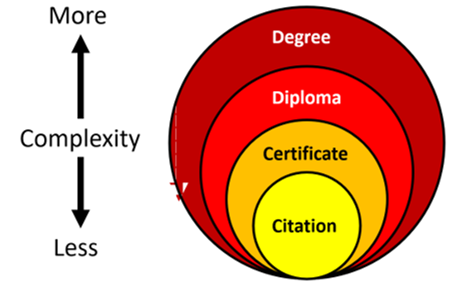

Program Learning Outcomes can support the guiding of the discipline. If the subject matter expert who teaches in the discipline feels that the discipline needs to move in a particular direction (for example, climate change, social justice, sustainability, etc.) then PLOs can be created to guide future graduates in these necessary directions. Most people writing Learning Outcomes want a specific number to act as a target. With Learning Outcomes quality is always more important than quantity. However, a very general recommendation can be 12 PLOs for a degree, six PLOs for a diploma, and three PLOs for a certificate ± 2 for each credential.

As Program Learning Outcomes describe the abilities of graduates upon the culmination of their program, the type of program the graduates are completing also impacts the Program Learning Outcome.

CREDENTIAL INFLUENCES ON PLOS

The level of credential can influence the development of the Program Learning Outcome. Certificates on average require the completion of 30 credits and are often intended as an introduction or to provide a survey of material for the discipline. Certificates tend not to be very broad or deep in their exploration of a disciplined material. Bachelor’s degrees require the completion of 120 credits, on average, and provide both a breadth of information and an exploration of that information in depth.

Often credentials are intended to ladder into one another. That means a 30-credit certificate will ladder directly into a 60-credit diploma, which in turn ladders directly into a 120-credit degree. In other words, the 30 credits completed as part of the certificate act as the first 30 credits required by the diploma. If a discipline offers credentials at multiple levels, it is generally safe to assume that the material required by a lower credential is included in the higher credential. If a department offers credentials at different levels in the same discipline, it is reasonable to assume that a certificate’s requirements are included in the diploma, and the diploma’s requirements are included in the degree. It’s reasonable to assume that the material covered increases in complexity from a credential requiring fewer credits to a credential requiring more credits. The notable exception is for those certificates intended to provide specialized information for people who have completed a previous credential. In these cases, the certificate may cover advanced and complex information that is narrow in scope to provide a specialization to the graduate.

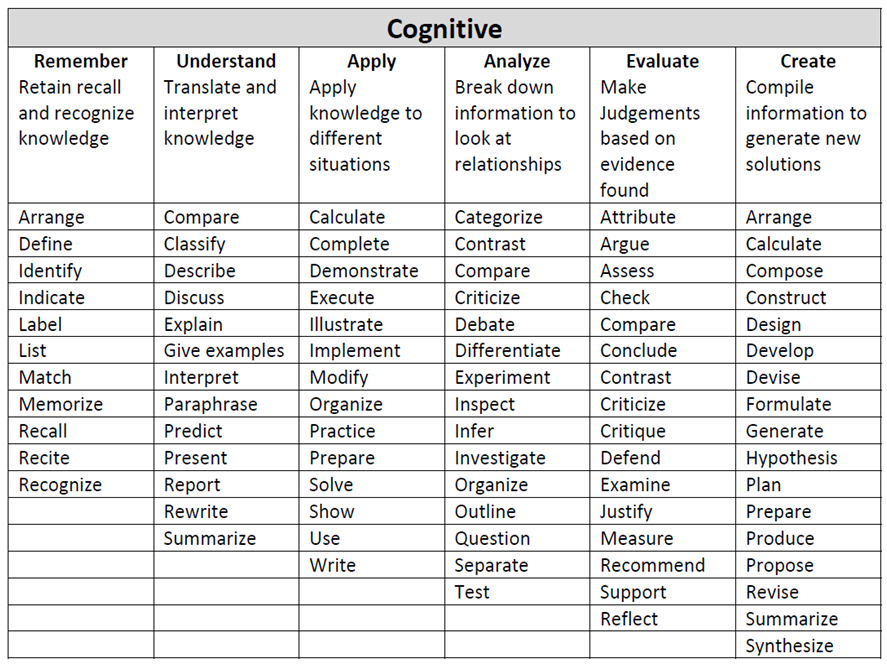

Understanding the different intention of the credential and the resulting different experience with the material is an important consideration when developing a Learning Outcome for the program. The verb, KSA and indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated chosen for the Learning Outcome will be different for a program resulting in a certificate than for a program resulting in a degree. Generally speaking, verbs chosen for Program Learning Outcomes at the certificate level will be selected from the first two levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy while verbs chosen for Program Learning Outcomes at the degree level we’ll be selected from the last three levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The KSA may change for a Program Learning Outcome at the certificate level compared to a Program Learning Outcome of the degree level depending on the specific KSA chosen. The indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated will increase in complexity for a Program Learning Outcome at the degree level from a program we’re going to come out of the certificate level. Here are examples of Program Learning Outcomes developed for the certificate, diploma and degree levels:

Certificate level PLO

After successfully completing the Certificate in Fine Arts, graduates will be able to describe a specific art piece’s role as social commentary.

Diploma Level PLO

After successfully completing the Diploma in Fine Arts, graduates will be able to contrast social influences that differentiate artists from each other within and across art periods.

Degree level PLO

After successfully completing the Degree in Fine Arts, graduates will be able to Experiment in the development of an independent artistic voice and practice through visual, written, and verbal communication.

In these examples, the verb choice increases in complexity and Bloom Taxonomy level from certificate through diploma to degree. While the KSA for each PLO describes the idea of using art to communicate, the specific KSA differs and increases in complexity from certificate through diploma to degree. Finally, the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated changes significantly in both scope and depth from the certificate level through the diploma level to the degree level.

Caution about Developing/Revising PLOs for Current Programs

Before embarking on any changes to PLOs of current programs please consult with the Office of the Provost and Vice-President Academic at oProCurriculum@kpu.ca. The Provost’s Office can advise on the potential regulatory or policy implications of Program Outcome changes – including the determination as to whether the Provost might need to consult the Ministry of Post-Secondary Education and Futures Skills about particular, significant, program change proposals.

Course learning outcomes

As discussed earlier, Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs) are Learning Outcomes from educational activities that occur at the course-level. Learning Outcomes describe a student’s ability at the culmination of an educational activity, therefore all Course Level Learning Outcomes will speak to a student’s expected ability upon completion of the course. Courses may appear at any level of the program. Some courses will introduce foundational material that other courses will reference and develop, and finally, other courses will refine this material to a very advanced state. It’s reasonable to assume that a student’s ability upon the culmination of a course with the material taught at the introductory or foundational level will be much less complex than a student’s ability with material taught at an advanced level. For this reason, Course Learning Outcomes are more challenging to create than Program Learning Outcomes. The verbs, and Indication of how a KSA will be demonstrated for a PLO will only be at the highest possible level of Bloom’s Taxonomy for the credential. The verbs and indication of how a KSA will be demonstrated for a CLO can be at any level of complexity below that of the PLO. When creating a Course Learning Outcome, the subject matter expert team must be deliberate in assessing the level of complexity of the course, where it will appear in the program progression (often indicated by the course number), choose a verb from the appropriate level of Bloom’s Taxonomy and an appropriately complex indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated.

As the Course Learning Outcomes represent the student’s ability upon culmination of the course, the Learning Outcomes are less likely to document specific learning tasks. Instead, CLOs acknowledge the students’ ability to synthesize information from across the course and apply it to in-class assessments, activities and out of class demonstrations.

CLOs tend to be very aligned with the summative assessments for a course. This is supported by backward design and constructive alignment, discussed earlier. Considering the conditions and criteria can assist the subject matter expert in aligning the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated with the assessment. As a reminder, the conditions speak to how/where the learning will take place or be demonstrated. The criteria speak to how well the learning must be demonstrated for learning to have happened. Both the condition and the criteria require a demonstration of learning, and this demonstration can be assessed. Since the conditions and criteria of the CLO and the assessment are so closely aligned, it can be helpful for the subject matter expert team to develop them together. Some subject matter experts will develop their assessments alongside the development of their outcomes using a table like the one pictured below.

CLO Development Table

Sentence stem. By the end of this course, the student will be able to….

| Measurable Verb | KSA | Indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated | Assessment | |

| CLO#1 | List | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | In the order of their progression | Short answer question. T or f/multiple choice quiz |

| CLO#2 | Infer | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | Which stage a subject is in based on their behaviour | Written response detailing stage and support for analysis. |

| CLO#3 | Characterize | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | The thoughts and feelings of subjects in any stage, | Creation of a written or visual representation of a subject experiencing a stage. |

Looking at the above example all components of the Learning Outcome structure are evident. From Bloom’s Taxonomy and reviewing the verb choices it is evident that CLO 1 and 2 both take place within the cognitive domain and CLO 3 takes place in the affective domain. It is also evident that the Learning Outcomes increase in complexity from number one through number three. As a result, the assessments also increase in complexity from number one through number three. In this way the assessments are in alignment with the Learning Outcomes, as constructive alignment recommends. The assessments indicated are intended to provide guidance, they are not intended to be restrictive. Any instructor following this Course Learning Outcome and assessment development table are able to develop their own assessments if they choose to, and the table provides some guidance regarding the level of complexity that their assessment should represent.

DEVELOPING/REVISING CLOS

When developing a curriculum, Program Learning Outcomes are generally developed first followed by Course Learning Outcomes. When it comes time to assess a curriculum for quality, the curriculum is often assessed based on the intersection between the KSA’s of the Course Learning Outcomes and the Program Learning Outcomes. If a course’s Learning Outcomes do not intersect or are not in alignment with any of the Program Learning Outcomes, then the question arises “what is the purpose of the course for the program?”. It is important to consider the alignment of Course Learning Outcomes to Program Learning Outcomes when developing or revising Course Learning Outcomes. These intersections are a critical component of Curriculum Mapping.

See link to the curriculum mapping resource that will further explain this process

As with PLOs there are no set number of CLOs required for a course. Quality is more important than quantity in this case, and subject matter experts may use five CLOs per course (± 2) as a general target.

Lesson learning outcomes

As discussed earlier, Lesson Learning Outcomes (LLO) are Learning Outcomes from educational activities that occur at the lesson level. As Learning Outcomes describe a student’s ability at the culmination of an educational activity, all Lesson-Level Learning Outcomes will speak to a student’s expected ability upon completion of a lesson. A lesson can appear in any course, and as discussed earlier courses may appear at any level of the program. This means that, similar to CLOs, LLOs can use verbs from any level of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Lesson Learning Outcomes articulate the overall ability available to learners engaged in a lesson. LLOs will speak to specific learning tasks from discreet and granular, through to complex and nebulous.

DEVELOPING/REVISING LLOS

As Course Learning Outcomes are designed to align with Program Learning Outcomes, Lesson Learning Outcomes are designed to align with Course Learning Outcomes. Each Lesson Learning Outcomes should lead towards the achievement of at least one Course Learning Outcome. If an LLO does not support a CLO, then its presence must be questioned. Lesson Learning Outcomes should be developed in such a way as to encourage the progression of competency in a well scaffolded manner. The material that is foundational to the development of competency should appear earlier in the progression of the lesson than more advanced material. While Course Learning Outcomes speak to the abilities of learners who have access to all the material presented in the course, Lesson Learning Outcomes need appropriate progression from simple to complex or foundational to experimental.

Since the Lesson Learning Outcomes support the Course Learning Outcomes, the verbs chosen for an LLO must be of equal or lower complexity on Bloom’s Taxonomy to the Course Learning Outcomes that the lesson supports.

Like Course Learning Outcomes, Lesson Learning Outcomes are closely aligned with assessments. In this case, these assessments are formative and diagnostic. Briefly, formative assessments provide feedback to the learner regarding how well they are performing in developing competency in the learning task. Diagnostic assessments provide feedback to the instructor regarding the learner’s competency so they may make an informed decision when to move on to the next learning task. Considering the conditions and criteria are helpful in developing the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated as well as the assessments that measure learning. For Lesson Learning Outcomes the conditions refer to how/ where the Learning or the demonstration of Learning takes place. The criteria refer to how well learning must be demonstrated for Learning to have happened. The subject matter expert developing the Lesson Learning Outcome must consider how the competency with the learning task will be demonstrated and how well it must be demonstrated to move on to the next learning task.

Generally speaking, Lesson Learning Outcomes are the last outcomes to be created. Program Learning Outcomes influence the development of courses which lead to Course Learning Outcomes, and Course Learning Outcomes influence the development of lessons which lead to lesson Learning Outcomes.

Before discussing a target number of Lesson Learning Outcomes, some terms need to be operationally defined. These terms are “class” and “lesson”. For the purpose of this resource, the term class refers to the usual time frame spent delivering a series of lessons. This time frame is arbitrary to the learning process, defined by policy and indicative of a post-secondary environment. Classes may be two hours in length, three hours in length, or on rare occasions longer. Lessons on the other hand refer to the time and effort required for the learner to develop and display competency of the discrete learning task to the level that allows for progression as established by the subject matter expert who designed the lesson. “Course” therefore, refers to the time frame that the instructor and learners are gathered together, while “lesson” refers to the learning required to develop competency. With this understanding, it is evident that there may be one or several lessons completed within a class. There should be only one LLO for each discrete learning task, that is one LLO for each lesson. Several lessons may take place each class.

For more information and hands on experience developing lesson learning outcomes, please register for the instructional skills workshop. Information regarding the instructional skill workshop schedule and how to register is available here.

B. Alignment of Learning Outcomes

Assessments (Constructive Alignment: Next Steps)

This resource has discussed the importance of assessments both in constructive alignment and with specific Learning Outcome types. There is often confusion with people conflating the ideas of assessment and grading. The key difference between grading and assessment comes down to intention. Grading focuses on measuring individual student performance and providing points or letter grades to reflect this performance, while assessment focuses on improving skill competency and learning. Grading is more focused on meeting the needs of external agencies such as the institution, the ministry, and industry, while assessments are focused on supporting the learner to improve. It is important to note that not all assessments include grades, and the assessments most focused on facilitating learner competency development usually exclude grades.

There are thousands of types of assessments, but really only three purposes for assessments.

Assessment purposes include:

Diagnostic

Diagnostic assessments are used at the beginning of the educational activity to measure the learner’s current KSA competency. This allows the instructor and the opportunity to tailor the material to the competency level of the learner. If the learners are more advanced than expected the instructor can increase the level of complexity of the educational activity. If the learners are less advanced than expected, the instructor can decrease the level of complexity of the educational activity. If learners are met with material that is too advanced, they can become lost in the educational activity as it has not been scaffolded properly to their level. Conversely if learners are met with material that they have progressed beyond, then they may lose interest due to boredom. Tailoring the material to the level of the learner facilitates engagement participation and maximizes learning potential. Using the same diagnostic assessment at the end of a lesson clearly demonstrates for the learner and the instructor that learning has taken place. Any positive difference in learner performance between the two diagnostic assessments is due to the educational activity and is evidence of learning. Diagnostic assessments are usually ungraded. Diagnostic assessments are often used in both lessons and courses.

Formative

Formative assessments are used to provide feedback to the learner on how well they are progressing with the material being taught in the educational activity. Formative assessments are also referred to as “assessments for learning”, emphasizing their purpose in Providing learners with an indication of their performance. Formative assessments tend not to have any value or grades assigned to them. In formal post-secondary education, Formative assessments may have a nominal value assigned to them to encourage learner participation. Formative assessments are most often used with learning tasks in lessons and are most closely aligned with LLOs.

Summative

Summative assessments are formal and final assessments used to measure a student’s performance in the educational activity and provide a grade reflective of this performance. For this reason, summative assessments are often referred to as “assessments of learning”. Summative assessments may occur only at the end of an educational activity or in intervals to measure performance at specific points in the educational activity. The defining characteristic of summative assessments is that they are graded and therefore high stakes. Summative assessments occur most often in courses and are highly aligned with CLOs. In rare cases, such as comprehensive examinations in professional programs, will you find a summative assessment at a program level.

As indicated earlier it is recommended for subject matter expert teams to develop their summative assessments alongside the development of their Course Learning Outcomes.

As a reminder, when developing the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated, considering the conditions and criteria can support the development of the assessment. The conditions speak to how or where the learning will be demonstrated, and the criteria speak to how well the demonstration must take place for Learning to have happened. Both the condition and the criteria require a demonstration of learning, and this demonstration can be assessed. Since the conditions and criteria of the CLO and the assessment are so closely aligned, it can be helpful for the subject matter expert team to develop them together. Some subject matter experts will develop their assessments alongside the development of their outcome using a table like the one pictured below.

CLO Development Table

Sentence stem. By the end of this course, the student will be able to….

| Measurable Verb | KSA | Indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated | Summative Assessment | |

| CLO#1 | List | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | In the order of their progression | Short answer question. T or f/multiple choice quiz |

| CLO#2 | Infer | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | Which stage a subject is in based on their behaviour | Written response detailing stage and support for analysis. |

| CLO#3 | Characterize | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | The thoughts and feelings of subjects in any stage, | Creation of a written or visual representation of a subject experiencing a stage. |

For more information about diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments please explore our asynchronous resource, Foundations of Teaching Excellence (FTE). This resource covers assessment purposes in depth as well as specific classroom assessment techniques and strategies. In addition to the module on assessments this asynchronous resource also provides in depth information on the use of learning design, learning technologies, and inclusive teaching wrapped up in reflective practice.

Instruction (Constructive Alignment: Next Steps)

At this point in the resource we have extensively covered Learning Outcomes and have explored assessments of learning. Looking back to the beginning of this resource where the process of outcome-based education was discussed, nine steps were identified. As a reminder these steps are:

Steps 1 through 3 articulate the creation communication and review of Learning Outcomes. Steps 4, 6, 7, and 8 refer to the development of assessments and grading rubrics, administering the assessment, evaluating the students’ performance and assessment of the students’ achievement of Learning Outcomes. All of these steps have been covered by the resource so far. The two steps that have not been addressed by the resource are:

Step 5: develop instruction designed to have students meet these goals, and

Step 9: reflect on why your students did or did not achieve the learning goals and develop strategies to help them be as or more successful in the future.

The final step required for constructive alignment in curriculum is to identify and develop instructional strategies, techniques and practices that are designed to support your learner’s demonstration of the Learning Outcome on the designed assessment. Again, this isn’t the same thing as teaching to the test, instead it is deliberately planning to address the material required to demonstrate achievement of Learning Outcome in the way that the assessment measures it. For example, the Learning Outcome may state: “by the end of this lesson the student will be able to reproduce a G chord on the piano with their left hand.” from this Learning Outcome it is possible to extrapolate an assessment where the student uses their left hand to play the notes of a G chord on the piano. An aligned instructional activity will likely involve some discussion around the notes required for a G chord, which keys correspond with those notes and some practice where the student practices playing each note in unison to create a G chord sound. An instructional activity that is not aligned with this outcome or assessment may include the learner drawing the finger positions required for a G chord on a printed representation of a keyboard, or a discussion of the emotional tone conveyed by songs written or performed in the key of G. Both of these instructional activities present new information to students. Both of these instructional activities also speak to the representation of the G chord and may be valuable instructional techniques or activities in their own right. Unfortunately, due to the Learning Outcome and it’s aligned assessment, these instructional activities will not support the student’s achievement of the Learning Outcome nor perform well on an assessment that measures the achievement of that Learning Outcome.

If the Learning Outcome were changed to be: “by the end of the lesson the student will be able to describe the emotional nuance imparted to pieces of music played in the G chord”, and the assessment to: “students will draft a paper detailing their position and present real-world examples of pieces delete one-word musical pieces in the key of G to support their argument.” Our other instructional technique of: “a discussion of the emotional tone conveyed by songs written or performed in the key of G” is now in alignment with both the Learning Outcome and the assessment and represents equality aligned curriculum.

It is important to note here also that constructive alignment lives at many levels of educational structure. The more concrete the educational structure is for example, lesson level, the easier It is to develop the components of constructive alignment. The more abstract the educational structure, the more challenging it is to develop the components of constructive alignment. There is value to align curriculum at each relevant structural level, so it is worthwhile investing time in understanding and developing the components for constructive alignment at each of these levels.

One thing to consider that may help make this easier to conceptualize is the interaction between the line of competency development and higher levels of educational structure. The example given above described the line of competency development as it existed between Lesson Learning Outcomes and Course Learning Outcomes on its way to achieving the Program Learning Outcomes. The subject matter expert team should be able to identify the line of competence and development that achieves the Learning Outcomes that exist out of education structural level higher than program; that is institutional, and ministry. Once this line of competency development has been identified it is easier to identify the assessments or learning activities that were previously only implied. Once the assessments and learning activities of the higher structural levels are identified, they can be assessed for constructive alignment and modified to bring them into alignment.

Finally, while not a part of constructive alignment theory, step nine speaks to the idea of reflective practice. Although the subject matter expert worked to create an aligned curriculum, the achievement of an aligned curriculum is determined through its use. Only through reflecting on the intentions of the curriculum, and the students demonstrated performance can we be sure that our curriculum has met our goals. If we have met our goals with our curriculum this is a good opportunity to remind ourselves of what we are doing well, and if our curriculum has not met our goals comment this is a good opportunity to make some iterative changes in advance of the next offering of the curriculum. Through engaging reflective practice instructors become much more aware of their strengths, areas of challenge, and pathways to improvement. For more information about reflective practice please explore our asynchronous resource,

Steps in Developing Learning Outcomes

Having discussed the structure of learning outcomes and details related to the types of learning outcomes, this section will now explore steps in developing learning outcomes. There are nuanced differences in the steps when developing program level, course level and lesson level outcomes. This resource points towards only the general steps. Users are encouraged to register for program and course learning outcomes workshops to learn the specific of this process.

LINE OF COMPETENCY DEVELOPMENT

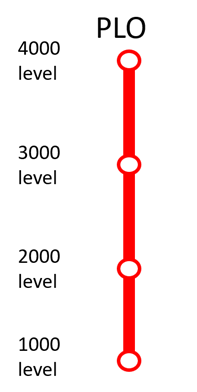

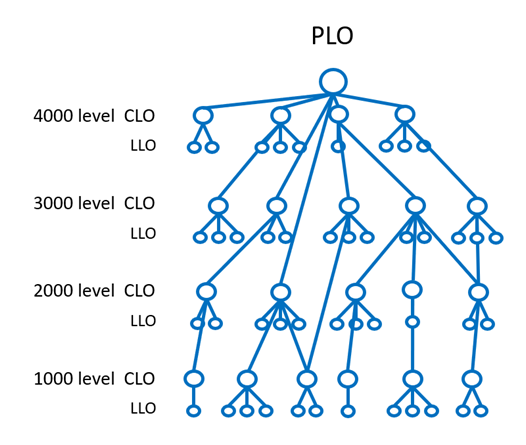

Competency and competency development have been mentioned several times in this resource. Briefly stated competency refers to the skill level of a learner with a KSA featured in an objective. People often have the assumption that the progression of a learner’s competency with the KSA is linear, As shown in Figure 1. That one Course Learning Outcome leads into the next Course Learning Outcome and eventually into the PLO. This assumption is not accurate. As stated earlier, Program Learning Outcomes are supported by Course Learning Outcomes. If a Course Learning Outcome does not support a Program Learning Outcome directly, the Course Learning Outcomes existence needs to be questioned. Similarly, Lesson Learning Outcomes must support Course Learning Outcomes. Therefore, all Lesson Learning Outcomes will support Program Learning Outcomes.

In the context of a formal program resulting in a credential, it has been In the context of a formal program resulting in a credential, it has been recommended to target 12 Program Learning Outcomes for an undergraduate degree. This undergraduate degree will be at least 120 credits or 40 courses across four academic years. Previously this resource recommended a target of 5 CLOs for each course. This results in 200 individual Course Learning Outcomes feeding into 12 Program Learning Outcomes. Earlier it was suggested that the number of Lesson Learning Outcomes required are course specific. It is reasonable to assume that a lesson will not extend beyond the time limits of a class; if anything, multiple lessons will exist within the time limits in a class. At KPU we tend to have 13 weeks’ worth of classes per course, however, Statutory holidays can reduce this to as few as 10 weeks of classes per course. Proceeding conservatively, assuming a minimum of one Lesson Learning Outcome for each class, and a minimum of 10 classes for each course, it is reasonable to conclude that each course will consist of a minimum of 10 Lesson Learning Outcomes. Ten Lesson Learning Outcomes for 200 individual Course Learning Outcomes means a degree program at KPU will have a minimum of 2000 discrete Lesson Learning Outcomes supporting 12 PLOs, or an average of 167 LLOs for each PLO. The reality is LLOs often support more than one CLO and CLOS often support more than one PLO. This overlap significantly increases the numbers in practice, yet the minimum possible is 167 LLOs for each PLO. This provides some insight into how complex, branching, converging, and diverging the path of competency development is for any PLO.

It is possible to map a learner’s competency development with a particular KSA from lesson learning outcome, through Course Learning Outcome and to Program Learning Outcome. The progression of the Competency development may appear linear using Lesson Learning Outcomes as a starting point and Program Learning Outcomes as a finishing point, it is important to remember that Learning Outcomes are developed at the program level first, followed by the course level, and finishing with the lesson level. Using the PLO as a starting point, working through CLOs and on to LLOs, the path becomes extremely complex, as shown in figure 2.

As a subject matter expert team working to develop Learning Outcomes for a program, the courses that make up the program, and the lessons that make up the courses, it is important to note the path of competency development is complex with converging and diverging branches across lessons and courses leading to one or more PLOs. This also makes clear how broadly a PLO must be written to account for 166 individual learning tasks.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER – OUTCOMES DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT KSA’s

Before Learning Outcomes can be written, relevant competencies need to be identified. Competencies are the goals of your educational activity. These are often thought to be the same as the knowledge, skill, or attitude the learner will be able to demonstrate upon culmination of the educational activity. Competencies exist at all levels of educational structure and inform the outcomes at those levels. for example, competency at the program level will outline knowledge skills or attitudes that are required for a graduate or a program to be considered successful. Competencies at the course level will detail introductory, developing, or advancing capacity around relevant knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Finally, competencies at the lesson level will detail specific learning tasks required to achieve the relevant knowledge skills and attitudes.

In the context of higher education curriculum, “imposed” and “motivated” competencies are technical terms. “Imposed” competencies refer to the standardized skills and knowledge set outside of the department, while “motivated” competencies are those driven by students’ own interests and learning goals. Balancing these competencies is a significant aspect of curriculum development and implementation, ensuring both standard compliance and individual learning needs are met (Chan, Fong, Luk, & Ho, 2017).

Competencies tend to fall into two categories, these are:

Imposed Competencies

Imposed competencies refer to the external requirements for an educational activity. In the lesson this would include learning tasks that are unrelated to the discipline or the content that must be covered before access to the content can begin. An example of this would be lab safety protocols that students must know before being able to work with certain volatile chemicals in a chemistry class. Similarly, in a woodworking course, there may be safety requirements or training that must be completed before the students will be allowed access to powered machinery. Imposed competencies at the course level are items that are unrelated to the specific content being covered yet are required for progression or assessment purposes. This could include things like introduction to citation formats required for presentations, group work, or essays. This could also include things like mandatory library or IT workshops. Finally, imposed competencies at the program level include items that need to be met that are distinct from the discipline or are required for the learner to progress beyond the program of study. This could include items such as requirements imposed by regulatory bodies for students to gain employment in a particular field. Please keep in mind that Kwantlen Polytechnic University has its own set of imposed competencies for programs outlined in policy AC9.

Motivated Competencies

Motivated competencies are the knowledge skills and attitudes that educators and students want for their learners and for their learning. Students will have a clear understanding of what they want from their program, course, and lessons that support their study, progression, and career. Students however may not have a clear perspective on How to prepare for future needs, such as career advancement, and participation in society. Educators generally have a broader perspective and can identify competencies that students don’t recognize they need. This may include things like formal communication skills, leadership, research or teaching skills.

In any event, the subject matter expert team needs to develop the competencies that will inform their educational activities outcomes. While developing competencies for the lesson level is relatively easy with one or two colleagues representing the subject matter expert team, developing competencies for the course and program levels are significantly more complex given the scope of the task.

AFFINITY DIAGRAM PROCESS TO GENERATE COMPETENCIES

As described earlier, curriculums are extremely complex with thousands of possible Learning Outcomes in a four-year degree. It is a daunting task to brainstorm or generate competency suggestions in the face of such enormity. For this reason, the Teaching and Learning Commons recommends using an affinity diagram process to generate competency ideas. This process has been tested and found to be effective in generating Learning Outcomes at the program level, course level, and lesson level, with some level specific modifications. The next section of this resource will detail the use of an affinity diagram in developing Learning Outcomes at all three levels. It will be noted in detail, where a level specific modification is required.

Steps required for an Affinity Diagram:

WRITING LEARNING OUTCOMES

As a reminder there are four structural components that make up Learning Outcomes. These are:

A Sentence Stem

The question asked of the subject matter expert team when they were developing the list of competencies will inform the sentence stem. In most cases it will act as the inverse of the question asked. For example, if the question asked of the subject matter expert team is, “what does a graduate of a science degree majoring in biology need to know or have been introduced to?” then the stem that answers this question would be “a graduate of science degree majoring in biology will be able to…”. If the question asked of the subject matter expert team was “What does a student who has completed biology 1110 need to know or have been introduced to?”, then the stem that answers this question would be a student who has completed biology 1110 will be able to…”.

The sentence stem will be the same for every outcome related to the educational activity in question. If the sentence stem is for a Program Learning Outcome, then this stem will be the same for all Learning Outcomes associated with this program. If the sentence stem is for a particular course, then all the Course Learning Outcomes for this particular course we’ll share the same sentence stem.

Measurable Verb

This was passed over earlier as KSAs are easier to identify, and the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated or assessed is often required to determine the appropriate verb. Review the KSA and its indication of how it will be demonstrated or assessed. Try to determine the domain of learning this describes. With the domain of learning identified, review the Bloom’s Taxonomy documents and find the category that best describes the level and complexity intended by this outcome. With the level identified, select the verb that best describes the demonstration or assessment for the KSA in question.

Where possible, use the verbs that are indicated in the Bloom’s Taxonomy documents. This will help keep Learning Outcome language consistent across departments disciplines and the institution. If the subject matter expert team selects a verb that does not appear on the Bloom’s taxonomy documents, and has a rationale for the choice, then use the new verb.

it is important to note that the development of Learning Outcomes is a complex and nuanced process. It will take the subject matter expert team a fair amount of time to generate and revise Learning Outcomes, to the point that they are structurally sound and meaningful.

With all the components of the Learning Outcomes identified, the subject matter expert team may choose to consider identifying aligned assessments, it may be helpful to use a table to support this like the provided below.

KSA (Knowledge, Skill or Attitude)

As KSAs are similar to competencies, and the subject matter expert team has just identified a significant list of competencies, it is often easier to move to competencies after identifying the sentence stem. Review the list of competencies and the categories of competencies identified on the list. The category titles are the best place to start to identify the KSA for an outcome. In many cases, the category title will be the KSA used for the outcome. In some cases, the category is too broad and is best represented by two outcomes. Remember back to our guiding questions and try to select the KSA that best represents the most enduring Learning demonstrable upon culmination of the educational activity.

Indication of how the KSA will be Demonstrated or Assessed

With the KSA for the outcome identified, Attention can be paid to describing how the KSA will be demonstrated or assessed. Again, the subject matter expert team should consider the questions that were asked in the generation of the competencies. Consider; “What knowledge or skills do the learners bring to the activity?”, “What knowledge or skills will be built on?” and “How can the enduring learning be demonstrated?”. When considering these questions, thought should be given to the intended level of the educational activity, and what competencies need mastery to progress.

This component of the outcome structure can be difficult to describe. It may be helpful to consider the conditions under which the demonstration or assessment may take place and the criteria the demonstration or assessment must meet for learning to be considered to have occurred.

EXAMPLES OF LEARNING OUTCOMES GENERATED

Learning Outcomes and Assessment Table

Sentence Stem. By the end of this <educational activity>, the student will be able to….

| Measurable Verb | KSA | Indication of how the KSA will be Demonstrated | Aligned Assessment | |

| LLO | Describe | Piaget’s Formal Operations stage of development | When prompted in class including 5 key descriptive factors. | In class diagnostic. Verbal question and answer |

| CLO | Infer | Kübler-Ross’ 5 stages of grieving | Which stage a subject is in based on a description of behaviour | Essay question on exam. Written response detailing stage and support for analysis. |

| PLO | Apply | Knowledge of theories, concepts and key findings in Psychology | To everyday issues and situations. | Post Program. Social interactions, Career situations, applications for grad school, |

COMMON PROBLEMS WITH LEARNING OUTCOMES

Now that you have explored components of a structurally sound Learning Outcomes, the following is a table which will showcase several common problems noticed in Learning Outcomes and possible solutions. This is not a comprehensive list, and it provides a good example of the most commonly experienced issues.

Examples of Common Learning Outcome Problems and Solutions

| Problem Learning Outcomes | Better Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Not Student Centered | Student Centered |

| Different theories of economic development will be explored through lectures, readings and assignments. | Students will describe each theory of economic development and the key characteristics that distinguish each theory. |

| Not Measurable | Measurable |

| Students will understand foreshadowing. | Students will be able to identify examples of foreshadowing in English literature and incorporate foreshadowing in their own works. |

| Unclear | Clear |

| Students will be able to analyze plants. | Students will be able to analyze climate characteristics of various plants making appropriate recommendations for green roof projects in specific cities. |

| Not Concise | Concise |

| Students will describe the process to Weld aluminum in a shop, in the open air, in the rain, in the cold and in extreme heat paying attention to the specific material preparation and equipment required for tig welding, mig welding, and arc welding with recently prepared material versus material prepared more than two weeks ago. | Students will weld aluminum successfully in the environments they are likely to experience. |

| Double Barreled Verb | Single Verb Outcome |

| Students will be able to list, explain and show the 8 step to give an injection. | Students will be able to demonstrate the 8 steps used to administer an injection. |

| Task Based Inflexible | Outcome Based Flexible |

| Students will be able to demonstrate on an injection pad the 8 steps to give an injection. | Students will be able to demonstrate the 8 steps used to administer an injection. |

Common Learning Outcome Problem #1: Not Student Centered.

This Learning Outcome is describing the actions of the instructor, not the demonstrated student learning. This is a problem because it guides future learners and instructors to focus on the material that will be covered rather than focus on supporting the students learning. To fix this, rewrite the objective from the perspective of the student. Including a sentence stem that ends in “the student will be able to” will ensure the Learning Outcome is student centered.

Common Learning Outcome Problem #2: Not Measurable.

This Learning Outcome uses one of the forbidden verbs, “understand”. It is impossible to measure a student’s understanding without some other verb included. To fix this, rewrite the objective to include a measurable verb and detail how the student will demonstrate their understanding.

Common Learning Outcome Problem #3: Unclear.

This Learning Outcome is too general, and is lacking an indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated. There is no indication of how or where the analysis will be demonstrated or assessed. To fix this, rewrite the objective to include an indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated.

Common Learning Outcome Problem #4: Not Concise.

This Learning Outcome is too detailed in its indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated. As a result of including too many discrete venues of demonstration, the Outcome excludes all unmentioned venues. To fix this, rewrite the objective to concisely describe the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated.

Common Learning Outcome Problem #5: Double Barreled Verb.

This Learning Outcome provides too many actions that must be met for learning to have taken place. This leads to some confusion regarding Learning Outcome achievement, as it may be possible for a learner to achieve one verb but not the other. To fix this rewrite the objective to include only one verb. The verb to include should be the highest level of complexity according to Bloom’s Taxonomy of the verbs initially suggested. It is understood that adverb describing competency at a higher level includes the competencies described at lower levels as well. If the subject matter expert team feels the second verb needs to be specifically mentioned, write a second Learning Outcome with the verb.

Common Learning Problem #6: Task Based Inflexible.

This Learning Outcome confuses the KSA for the indication of how the KSA will be demonstrated. Doing this focuses the Outcome on the task rather than on the knowledge skill or attitude. This is one of the most common errors. It is often presented as something like “The Learner will use existing tools to develop unique solutions that meet client need.” Written in this way it looks like the verb is “use” and the KSA is “Tools”. This Learning Outcome is focused on the task of “using tools” rather than the KSA and its demonstration. To fix this rewrite the objective using the appropriate structure. This could be something like: “The Learner will develop unique solutions that meet client need by using the tools, resources and practices available.” Now the Verb is “Develop” the KSA is “Unique solutions” and the demonstration is “that meet client need”. This is more likely what the SME team intended when they created the objective. In some cases, the SME team wants to emphasize the use, understanding of and capability with industry specific practices and regulations. This can be achieved with the tag of: “by using the tools, resources and practices available”. It isn’t required to have a structurally sound Learning Outcome but can add some additional context regarding the intention of the educational activity.